Is Theo Von podcasting from the right or the left? That depends from where you’re looking.

When he sat with Donald Trump last summer in the run-up to the presidential election, he led a surprisingly affecting and humanizing conversation about drugs and addiction unlike any Trump had ever publicly had. But also: With Gabor Maté, a Canadian physician who has written extensively about the Middle East, the conversation about the thousands of children killed by Israel in Gaza reduced Von to tears.

Is Von compassionate or crude? With the professor and podcaster Scott Galloway, Von spoke openly about his struggles with pornography: “It was the first kind of interaction with women that I could manage.” But also: joking with Grace O’Malley, an up and coming comedian, about her romantic dry spell, Von assured her, “I think there’s a lot of semen heading your way in 2025.”

As an interviewer and the host of “This Past Weekend,” a podcast that routinely garners millions of views and listens, ranking among the most watched shows in the country, Von’s chameleonic chill is both his superpower and his mask. The result is a kind of lenticular effect — depending on the week, he’s a sophisticate or a naïf, one of the bros or a sly interloper.

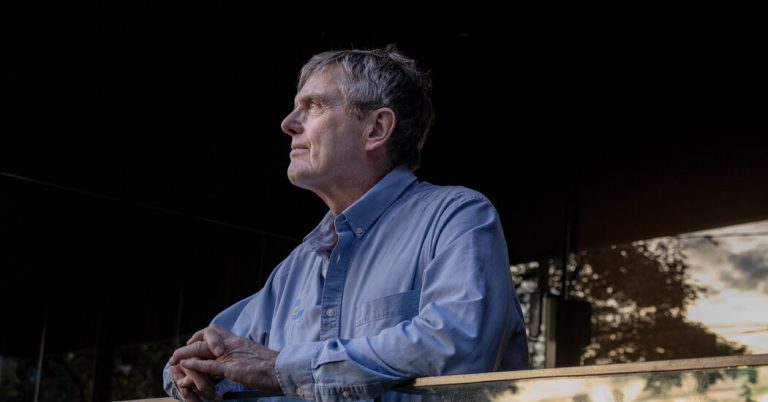

Von, an aww-shucks 45-year-old with hair somewhere between shag and mullet and a persistent mien of latent mischief, is often lumped into the inelegantly grouped “manosphere,” a loose aggregation of podcast hosts and social media figures — Joe Rogan being the sun of that solar system — whose politics lean rightward and whose attitude is allergic to doubt. They have built, in short order, a parallel mainstream media ecosystem, with personality-driven platforms that often let guests hawk their viewpoints unchecked, creating an echo chamber of boast and brag.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

Last month, when Von was a guest on the “Full Send” podcast, hosted by the MAGA-prankster Nelk Boys, he poked at their spacious moral window in regard to booking guests: “Finally somebody that’s not a sex trafficker on here.”

But unlike those peers, Von is pointedly tough to pin down, culturally or politically. His fear-free, lightly oddball and unselfconscious inquisitiveness and his comfort playing with jumbled signifiers — of political affiliation, race, class and more — make him a far more nebulous performer. Under the cover of the manosphere, he’s become one of the defining conversationalists in America.

Subscribe to The Times to read as many articles as you like.