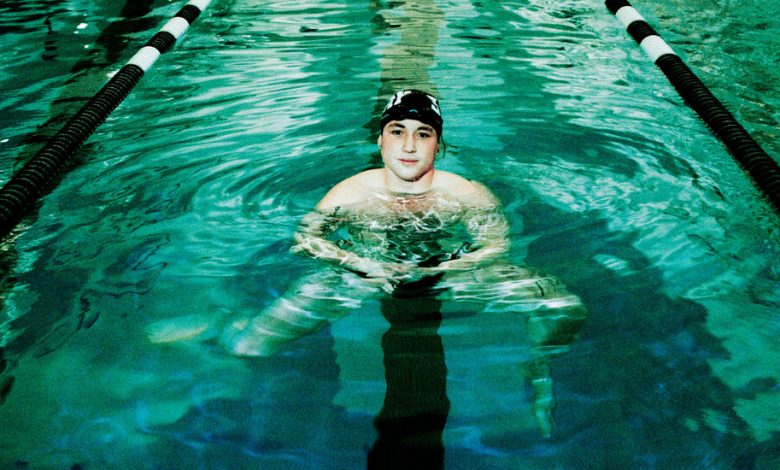

I’m a Trans Athlete. I’d Rather Be Myself Than Win.

The first time I remember feeling different from the people around me was in fourth grade. I felt like I’d been thrust onstage for a show without having been given a script. Every interaction seemed wrong. Recognizing my bisexuality in seventh grade gave me a degree of comfort, like a candle held out against dark confusion, but even then, so much of myself still felt impossible to discern.

Despite growing up in progressive California, it wasn’t until eighth grade that I met a trans person. He put words to feelings I hadn’t been able to name for myself, like how out of place he felt in his own skin or to be perceived as a girl. After reading other people’s stories of realization online, I was certain enough that I was trans to tell my mom that I was her son, not her daughter.

But I wasn’t ready to follow through and soon found myself retreating. I concluded that I should try to fit myself into an identity as close to “normal” as possible, to follow the path of least resistance.

Despite my best efforts to minimize my queerness, whispers of the “scary lesbian” followed me my first week at a new high school during my sophomore year. Because of my deeply internalized homophobia, being perceived as obviously queer felt like the worst thing that could possibly have happened as a new kid. I renewed my efforts to fit in, growing my hair out, wearing more traditionally feminine clothing and learning how to do my makeup. These changes didn’t help me feel better or more confident, but they shifted others’ perceptions of me.

With time, I got better at putting on a mask of womanhood. I peeked at the scripts my friends held and practiced their lines. The act of denying my true self became second nature. If you had asked me then, I would have told you I was a cisgender woman. I was completely out of touch with myself, ignoring how miserable I was inside.

I felt most appreciated and closest to my true self when I was swimming, the sport that I’d been doing competitively since age 4. In the water I could focus on the joy of racing. There is no feeling like pushing yourself to catch up to the person ahead of you, surprising yourself with what you’re capable of. My strength and musculature — traditionally masculine values — were celebrated.

When I was 14, my relay team broke a national age group record. A couple months later, I qualified for and competed in the 2016 Olympic team trials, though I ultimately was disqualified when I twitched on the blocks because of nerves. At 18, I was one of the top 20 high school swimmers in California and one of the top 100 swimmers in the country.

Credit…Avion Pearce for The New York Times

I valued the contributions I made to the team’s success. I built part of my identity around being a power player and enjoyed the respect given to hard workers and winners. I was able to define myself by what I could do beyond the norm, not by how well I could fit into it. I did not need to ask myself who I was the way I did at school or in social settings.

When I was recruited to Yale, I threw myself into the team-first ethos of college swimming. I focused more on scoring points and supporting my teammates and less on myself and my swim times. I frequently raced in relays, the most collaborative, fun part of swimming for me. I placed fourth in the 50 free at the Ivy League Women’s Swimming and Diving Championships my first season, and I was the highest point scorer on the women’s team in my sophomore year.

Despite these victories, my mere existence became effortful. I found friends and connected with other queer people on campus, but I felt like the women I knew understood something I didn’t. I felt the most discomfort in the locker room. It was a site of important team bonding: post-practice debriefs and chats that were women-only. But I could never focus on those things. I thought that my unease came from worry that my sexuality made others uncomfortable. I hadn’t yet considered that the real reason I felt so off was my sense of being in the wrong locker room.

When the pandemic hit the spring of my sophomore year, we were sent home from school. With the pools closed, I was stranded in my own head. I began questioning everything about myself again, stumbling through the darkness in my mind. I decided to take a gap year to focus on improving my mental health and, as an added benefit, to preserve my collegiate seasons of eligibility. If I had stayed I would have lost one of my seasons swimming for Yale.

I felt unsure of my identity, my life choices, my commitment to swimming — even unsure if I wanted to continue living. In order to survive, I tried to become the most ideal version of myself that I could picture at the time: a confident, empowered woman who was comfortable in her sexuality.

But the more I clung to womanhood, the worse I felt. Realizing this with the help of my therapist, I dived deeper into queerness, exploring the balance of masculinity and femininity, especially with presentation in clothing. Through that I discovered binders, base-layer compression garments used to create a more traditionally masculine chest appearance.

The first time I put one on, I tried on every tank top, T-shirt, sweater and hoodie I owned over it. “This is how I’ve always imagined my clothes fitting,” I thought. I felt euphoric.

Finally, I allowed myself to question my identity as a woman, letting the flickering questions grow into a bonfire against the dark.

It took me months after that to admit my transness to myself. I had internalized a lifetime of negative messaging around being trans. But the more I leaned into my authenticity, the easier I could breathe. Everything — even things that seemed unrelated, like doing work or going to the grocery store — felt easier. I allowed the current of my life to carry me instead of fighting it.

Stepping into myself was — and continues to be — a long process that has involved a new name and pronouns and a double mastectomy in early 2021. When I returned to campus that fall for my junior year, I had a big decision to make: Which team was I going to compete with for my last two years of college?

My coaches gave me the option of joining the men’s or women’s team, and my fellow swimmers on both teams were accepting of that. I had fast enough times to qualify as a walk-on for the men’s team.

Initially, I decided to stay with the women. I had made a commitment to that team. It was familiar, and I loved my teammates. I knew that transition didn’t need to include taking hormones; N.C.A.A. regulations require that athletes on testosterone-based hormone therapy compete on a designated mixed or men’s team.

I also understood that I would have been closer to the bottom of the pack on the men’s team.

But the incongruence of existing as a man on a women’s team was more difficult to navigate than I had expected.

The “let’s go, ladies!” cheers, the sign saying “WOMEN” as I entered the locker room, a slipped pronoun here and there and the itching wrongness of the women’s swimsuit I wore to race: They added up.

The Yale women swimmers are some of my best friends, but being on the team with them made explicit all of the ways I am not a woman. My mental health began to worsen again, and after a few months I confessed to a friend, “I don’t know if I can do this anymore.” We hadn’t even had our first official meet yet.

I came to understand that I didn’t belong on the women’s team. And I craved a space where I did belong.

Many people have reservations or even strong resistance to the participation of trans athletes in sports, particularly on women’s teams. I can understand why some people might worry about fairness or equality. But what seems to be missing from that conversation is our humanity.

It might not seem like such a big deal to swim on a team that doesn’t align with your true self. But think about how overwhelming it would be to spend 20 hours a week in a place where you feel you don’t belong. Eventually, for me, that reality made it hard to get out of bed to go to practice.

All athletes should be able to be their whole, authentic selves among their teammates and be able to play their sports without fear of discrimination.

I ended up having the best swim season of my life that year on the women’s team and went mostly undefeated. I won my first individual Ivy League title in the 50 free and, at my first N.C.A.A. championship meet, placed fifth in the 100 free, earning All-America honors.

I credit my success, in part, to a hard but vital choice I had already made for my final college season: to join the men’s team. I also started lifting weights with the men. The more time I spent with the guys, the more I realized how much better I felt in men’s spaces.

Now I’m a senior, swimming with the men. I’ve been taking hormones for almost eight months; my times are about the same as they were at the end of last season. Right before Thanksgiving we finished a meet against Ohio State, Notre Dame, Virginia Tech and others. I wasn’t the slowest guy in any of my events, but I’m not as successful in the sport as I was on the women’s team.

Instead, I’m trying to connect with my teammates in new ways, to cheer loudly, to focus more on the excitement of the sport. Competing and being challenged is the best part. It’s a different kind of fulfillment. And it’s pretty great to feel comfortable in the locker room every day.

I believe that when trans athletes win, we deserve to be celebrated just as cis athletes are. We are not cheating by pursuing our true selves — we have not forsaken our legitimacy. Elite sports are always a combination of natural advantage or talent and commitment to hard work. There is so much more to a great athlete than hormones or height. I swim faster than some cis men ever will.

I’ve been fortunate to receive so much support from my communities, especially from fellow trans athletes. I’m honored to be part of a group strong enough to withstand all of the undue attacks on our participation and personhood. Living in authenticity makes me a stronger, better man. Being trans is one of the least interesting things about me.

Feeling congruent with my team has opened my eyes even further to how powerful athletic communities can be and how important it is for everyone to have the chance to feel that.

Iszac Henig is a senior at Yale University majoring in earth and planetary sciences. He won All-America honors swimming for the women’s team in 2022.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.