The Many Lives of Jeannette Walls

ORANGE, Va. — Jeannette Walls could have had a life of leisure after the big success of her 2005 memoir, “The Glass Castle,” but she has too much energy for that. She walks fast and talks fast. Her laugh can be as loud as a gunshot.

She worked as a journalist in New York for nearly three decades and gave it up only when her book had spent months on best-seller lists. But even after more than 15 years in rural Virginia as a novelist who can send drafts to her editor more or less on her own schedule, she still seems like a reporter on deadline.

On a chilly gray afternoon at the end of February, she was behind the wheel of an all-terrain vehicle, driving down a rough path on the 320-acre property she owns with her husband, the nonfiction author John Taylor. She said she was going to show me the prize chestnut trees in the woods and the place where her parents were buried. Up ahead, Mr. Taylor was piloting a smaller and zippier ATV. The engines rumbled as the two vehicles rolled past the pond.

“I hope this doesn’t gross you out,” Ms. Walls said, “but the stew we’ll have tonight is venison. It’s from the property. The deer. The truth is, living in the country, I mean, I love animals, but you come to understand — there are just too many deer here, and they needed to be harvested. Our next door neighbor is the deputy sheriff, and he loves to hunt, so we let him hunt on our property. And he gives us the venison.”

Since “The Glass Castle” came out, Ms. Walls, 62, has published two novels, “Half-Broke Horses” and “The Silver Star.” Both were based on her own experiences or those of her family members. With “Hang the Moon,” which will be published on March 28, she is moving deeper into fictional territory. This one is an action-packed tale centered on a powerful family of moonshiners in 1920s Virginia, and it’s filled with enough dead bodies, doomed romances and sudden betrayals to make you wonder if George R.R. Martin had decided to ditch fantasy for Southern Gothic. It took her seven years to write.

These days, when Ms. Walls is not at her desk, she is focused on her land. She and her husband have been working with a biologist to encourage the return of native grasses, wildflowers and trees. There are also plenty of animals to take care of — 11 chickens, 10 cats, four horses and a pair of Saluki-Labrador mixes, Oliver and Raleigh.

“The Glass Castle” made it all possible. The story of her hardscrabble childhood — the days of going hungry, the nights of sleeping with no roof over her head — was not a story she really wanted to tell until she was 40 and Mr. Taylor encouraged her to get it all out in the open.

They got to know each other at New York magazine in the late 1980s, when she was covering Donald J. Trump and other local celebrities as the writer of the saucy Intelligencer column and he was cranking out feature stories. In those days Ms. Walls armored herself in big-shouldered power dresses while maintaining something of a cool distance from her colleagues. Mr. Taylor confronted her, saying he could tell she was hiding something.

She told him everything. Her father, Rex S. Walls, was a hard-drinking drifter who dreamed of inventing a gold-detecting gizmo that would make him rich enough to build a solar-powered glass castle for his family to live in. Her mother, Rose Mary Walls, was a hardy free spirit who hoped to succeed as a painter and abhorred the idea of bourgeois life. These two agents of chaos fought bitterly as they dragged their four children from town to town across the Southwest, leaving one place after another when the rent came due.

Out of luck and money, the parents left their brood in the care of Rex’s parents in his bleak hometown, Welch, West Virginia. The children were locked in a basement and made to use a bucket as their toilet. Meals were often cat food or whatever they could scrounge from garbage cans. In their late teens, Ms. Walls and her siblings escaped one by one to set up a new life in New York — only to be followed by their parents, who ended up living as squatters in the East Village as Ms. Walls covered the city’s movers and shakers. The first line of “The Glass Castle” neatly summed up her circumstances: “I was sitting in a taxi, wondering if I had overdressed for the evening, when I looked out the window and saw Mom rooting through a Dumpster.”

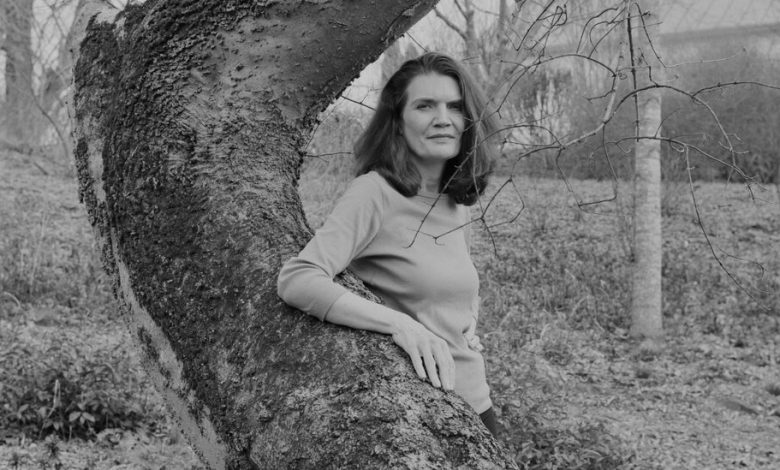

The author with one of her 10 chickens.Credit…Matt Eich for The New York Times

She wrote much of “The Glass Castle” while working as a gossip writer and red-carpet reporter for MSNBC and its website. The more she chronicled the latest on Lindsay Lohan, Britney Spears and Paris Hilton, the more she came to detest what she did for a living, and she was glad to put it all behind her once her memoir took off, she said.

“The Glass Castle” was not only a hit but the kind of publishing sensation that occurs once a decade or so. It was translated into 35 languages, spent 461 weeks on the New York Times paperback nonfiction best-seller list, and was made into a 2017 movie starring Woody Harrelson (as Rex Walls), Naomi Watts (as Rose Mary Walls) and Brie Larson (as Jeannette Walls). According to its publisher, the book has sold more than seven million copies in North America alone.

As Ms. Walls steered the ATV toward her parents’ graves, she mentioned the Keswick Hunt Club, a local group of tradition-bound fox hunters on horseback who sometimes gallop across the property while chasing down their quarry. When members of the club came upon the two graves on a recent excursion, they assumed they were part of a horse cemetery.

“So we’re held in great esteem for treating our horses that well,” Ms. Walls said with a big laugh.

Despite their differences, Ms. Walls invited her mother to join her and her husband in the Virginia countryside soon after they moved there in 2007. Rose Mary spent her last years in a newly built cottage behind the couple’s 19th-century Greek Revival house. She died on Aug. 21, 2021, at 87.

“Mom did not want to be cremated,” Ms. Walls said over the din of the ATV engine. “And I just couldn’t imagine putting her in a graveyard somewhere outside of town. She really wanted a green burial, and I thought it would be a lot of red tape — but it wasn’t at all.”

“And you know what?” she continued. “It wasn’t that bad. I thought it would be kind of traumatic, watching somebody die, but there was something kind of beautiful about it. I mean, she just had such joy up until the end. We’d put her in the ATV and put bungee cords around her so she wouldn’t fall out and drive her around the property. And she’d go, ‘Stop! Stop! Look at the color of that flower! Isn’t that beautiful?’”

Rose Mary was a prolific artist who produced all kinds of paintings — rural landscapes, urban scenes, abstract fantasias, portraits, still lifes — but she could not bear to part with them. At art fairs, she would tell prospective customers who came by her table that they couldn’t afford her work.

“Like a week before she died, she was painting,” Ms. Walls said. “In fact, we’ve got a whole damn garage full of paintings.”

She brought the ATV to a stop about 20 feet shy of two grassy mounds. They appeared to be almost melting into each other.

“So there they are,” Ms. Walls said. “Mom and Dad.”

Big laugh.

“It’s very pretty in the summertime,” she added. “There’s a deer lick near here, and there’s a really pretty stream over there.”

Employees of the nearby Preddy Funeral Home had done the digging, Ms. Walls said, noting that the burial was “legal and proper.” In keeping with her mother’s request, the morticians wrapped the body in cotton — no embalmment — and put it in a pine box.

Ms. Walls’s brother, Brian Walls, a retired New York Police Department sergeant, joined her and her husband for a casual ceremony. They placed some of Rose Mary’s paint brushes and paints on top of the coffin, along with her rosary and a small sculpture she had made of a horse.

A more elaborate process led to the placement of Rex at her side.

He had died in New York in 1994, at 59, of cardiac arrest after decades of alcoholism. A veteran of the United States Air Force, he was buried at Calverton National Cemetery in Riverhead, Long Island, a site operated by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Shortly after Rose Mary’s death, Brian Walls applied for and received a letter from Preddy Funeral Home certifying that he was acting as its agent. After approving the request, Veterans Affairs disinterred the body, placed the wooden coffin in a protective fiberglass case and fork-lifted it into the bed of Mr. Walls’s Ford F-350 pickup truck, Mr. Walls said. He secured it with yellow straps and drove his father’s remains from New York to Virginia. His dog, Sasha, a bulldog mix, rode shotgun.

“I did get a little side-eye at the Taco Bell drive-through,” Mr. Walls said.

He arrived at the property on a sunny October day. At the burial site Ms. Walls, Mr. Walls and Mr. Taylor said a few words and placed a notepad, pencil, slide rule and compass on top of the coffin. Rex and Rose Mary were once again side by side.

“I like it that Dad’s there,” Ms. Walls said. “They can argue.”

Something New

Readers of “The Glass Castle” know that Ms. Walls’s parents were not very big on the truth. Rose Mary said repeatedly that she had been pregnant with Jeannette for 11 months, a claim that never failed to infuriate her husband, and Rex held fast to his glass-castle dream against all reason.

When Ms. Walls became a journalist, she felt that she had at last cut herself off from the fantastic atmosphere that had suffused her chaotic upbringing. Facts anchored her. Comforted her. They also provided the grist for her column and her first book, “Dish: The Inside Story on the World of Gossip,” as well as her memoir and the two novels that followed.

Although “Hang the Moon” is more plainly a work of the imagination than anything else she has written, it is grounded in research. The heroine, Sallie Kincaid, who has ambitions to succeed her father as a rural political boss and whiskey dealer, is based to some degree on Willie Carter Sharpe, a woman who led moonshine convoys through Franklin County, Va., in the time of Prohibition and was known as the “Queen of the Roanoke Rumrunners.”

For the book’s overall plot, which concerns the passing of the leadership torch in a powerful clan, Ms. Walls used the story of the Tudor family as a rough template. Like Queen Elizabeth — and like Ms. Walls herself — Sallie Kincaid is underestimated in her youth, which only spurs her ambitions.

Walking toward the pond after putting the ATV back in the garage, Ms. Walls said she felt funny about straying from her journalistic roots.

“Both of my parents were fabulists,” she said. “They had these astonishingly active imaginations. And Dad was an astonishing storyteller. And he had these characters in his head that he would share with me all the time. And Mom, with her flexible realities. I just thought that the truth was sacred. I just clung to it.”

Beneath the head-spinning plot twists of “Hang the Moon,” historical research gives the novel its ballast. Because stock-car racing has its roots in the moonshiners who raced down back roads while making deliveries, she turned to “Driving with the Devil: Southern Moonshine, Detroit Wheels, and the Birth of NASCAR” by Neal Thompson. “Green’s Dictionary of Slang” was an online resource for period-appropriate diction and dialogue. Vintage letters and newspaper articles gave her a feel for the daily lives of country dwellers in the 1920s, as did her own childhood experiences.

“I feel that I’m more qualified than most Americans to write about this,” she said. “I know what it feels like to be without electricity. I know what a miracle it is to get these luxuries like flush toilets.”

Even with all the research, she said she found the writing of the book hard going. It took 17 drafts. She showed her work to her husband, the author of five books, “every step of the way,” she said. They sometimes acted out scenes together.

Her longtime editor, Nan Graham, the publisher and senior vice president of Scribner, told her to keep at it, although the early drafts were far from perfect or even publishable. “She would just draw a line through whole sections of what I’d written,” Ms. Walls said. “Just: ‘Take it out!’”

Things didn’t fall into place until she switched from the third person to first person, narrating the events in the voice of her protagonist.

“For whatever reason — and this is so stupid that it almost embarrasses me — but as soon as I put it in first person, I could kind of see and feel and think the things that she does,” Ms. Walls said. “It made all the difference in the world.”

Seeing skilled actors at work also showed her what she had to do to bring her characters to life.

“I was on the set of ‘The Glass Castle,’” she said, referring to the 2017 film, “watching those actors becoming somebody they’d never met. It was kind of a life-changer, talking to Woody trying to get inside the head of my crazy, drunken daddy, asking these really direct questions, just trying to get it, like: ‘Did he look you in the eye when he talked to you? What did he do with his hands?’ I said, ‘He crushed beer cans. Not wimpy beer cans like they have now but back when they were hard to crush.’ He said, ‘Like Cool Hand Luke!’”

“Honestly,” Ms. Walls continued, “when I first heard that Woody Harrelson was cast, I was like, ‘Really?’ He didn’t look much like Dad.’ But then the first time I saw him in character I started shaking. The first scene I saw them shooting was when my character, Brie Larson, was leaving, and Rex was trying to talk her into staying. It was just a surreal scene — my father, coming back like this. And then, here’s the thing: They went off-script. And Woody started saying things that my father had said that I hadn’t told him.

“Afterward, I mean, I was a mess,” she said. “I was slinging snot and everything. I don’t think he knew I was watching. He came by, and he saw me crying, and he started hugging me, and like an idiot I was apologizing to him, and he said, in Dad’s voice, ‘You don’t have to apologize, honey. You had to do it. You had to do it, or we wouldn’t be here.’ I was like, ‘Dang! Life is beautiful! My daddy’s come back from the dead, and I can apologize to him, and he can accept it.’”

Susan Beachy and Chris Harcum contributed research.