How the Claremont Institute Became a Nerve Center of the American Right

Listen to This Article

Audio Recording by Audm

To hear more audio stories from publications like The New York Times, download Audm for iPhone or Android.

“All weak sisters on the right must be called out,” wrote the editors of The American Mind on Nov. 5, 2020, in the uncertain days after the election. Their editorial, titled “The Fight Is Now,” warned that Democrats were all but declaring themselves the winners “before the votes are counted,” making a mockery of the law and trying to “demoralize half the country,” just as they had for the “last damned century.” But the 2020 election — like the contest for America’s future — was not yet over, they vowed. “The fight has just begun,” The American Mind declared. “This is the moment that decides everything.”

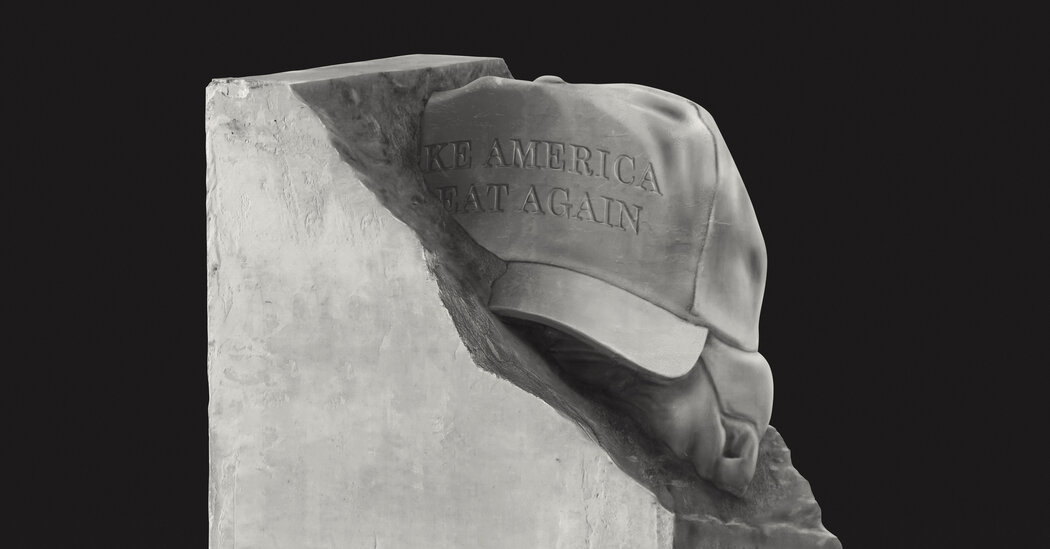

The American Mind is an online magazine of the Claremont Institute, a right-wing think tank in California that has, in recent years, become increasingly influential in Republican circles. Scholars at Claremont have long subscribed to the belief that the American republic has been dismantled, the Constitution corrupted by left-wing ideas, a viewpoint that is increasingly in step with that of the broader American right. In recent years, the Claremont Institute has also drawn attention for its deliberate provocations, most memorably with the publication in 2016 of “The Flight 93 Election.” The essay took as its guiding metaphor the only plane on 9/11 prevented from hitting its target by passengers who wrested control of the aircraft, arguing that the election that fall presented conservatives with a similar choice: either “you charge the cockpit” (i.e. vote for Donald Trump) “or you die.” In many ways, “Flight 93” was era-defining, abetting a reckoning within the conservative movement and prefiguring the take-no-prisoners style of right-wing politics that would soon hold sway.

Originally published under a pseudonym, “Flight 93” was written by Michael Anton, a Claremont senior fellow and a skilled polemicist, schooled, as he has written, in making “public arguments that move politics.” If his essay achieved anything, Anton told me, it was to turn Trump into a legitimate candidate of necessary change. “The initial assumption was: This guy’s a buffoon, a reality-TV star, not even an amateur politician, not a politician at all, there’s nothing serious about any of his ideas or any of his program, therefore no serious person could possibly support him or make an argument on his behalf, ” he said. “And then we did it.” Thomas Klingenstein, the chairman of the board at Claremont, went further, telling me that “if there is within the conservative movement a kind of intellectual justification for Trump, it comes from Claremont.”

The Claremont Institute is not a conventional think tank — comparatively small, its main outlets consist of two politics-and-ideas publications and several fellowship programs, including Publius and Lincoln, that have attracted rising stars on the right. Yet Claremont’s reach is extensive: Claremont scholars have collaborated with Ron DeSantis and helped shape the views of Clarence Thomas, Tom Cotton and the conservative activist Christopher Rufo, and the institute received the National Humanities Medal from President Trump in 2019. When Trump failed to win re-election, some Claremonters accused Democrats of using the pandemic to unconstitutionally change election laws to benefit themselves, and in “The Fight Is Now,” they called for “swarms of lawyers” to push for “transparency in all the Democratic city machines now churning out votes for Biden.” One lawyer who can be said to have taken up the challenge was John Eastman, a senior fellow at the institute for 30 years and the founder and director of Claremont’s Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence.

On Jan. 4 and 5, 2021, according to testimony during the Jan. 6 congressional hearings, as Donald Trump argued with his legal team over how much to participate in the march on the Capitol, Eastman, who was serving as outside counsel, debated with Mike Pence’s lawyer about two scenarios he had outlined, in which Pence could, on Jan. 6, reject disputed electoral slates already certified by the states. (Never mind that those slates were not actually disputed.) Pence’s lawyer, Greg Jacob, and other lawyers on the White House staff testified that they dismissed Eastman’s proposals as illegal and unconstitutional. On Jan. 6, as Pence was fleeing the Senate chamber for an underground location in the Capitol complex, Jacob fired off an email to Eastman, writing that after running “down every legal trail placed before me,” he concluded that Eastman’s framework was “essentially entirely made up.” Eastman had called Jacob “small minded” and castigated him for “sticking with minor procedural statutes while the Constitution is being shredded.”

If there is an unmistakable affinity between Eastman’s actions and Anton’s words in “Flight 93” — a sense of contemporary crisis — many scholars at Claremont place limits on the reach of that crisis-thinking. Eastman was working in a private capacity, and the Claremont Institute was not affiliated with his efforts to upend the 2020 election results. All the same, some of the arguments he advances hint at a shared genealogy of belief. Eastman told me that “what ails us in our body politic today — it’s the distortion of the founding principles,” a view that is widely held at Claremont. This explains, in part, Eastman’s actions, but also, increasingly, the tenor of the right.

Students of classical texts, Claremont scholars don’t always subscribe to the decorum once associated with Republican politics. Trump’s boorishness is of a piece with what some of them view as the rough-and-tumble nature of political life. “The philosophers that we tend to study are not deluded about this,” Anton told me. “Aristotle, in the treatise, explains how the actual practice of politics can be bare knuckle in lots and lots of ways.” On an American Mind podcast last year, Anton reflected that what is “too insufficiently remembered is that a lot of what went down in revolutions was rough stuff. We have a picture of dignified men in Independence Hall deliberating and debating. And all that happened, I don’t discount that. But there was a lot of other stuff going on, too.”

In this spirit, The American Mind began, in the months after Trump left office, to talk of “counterrevolution.” Glenn Ellmers, a senior fellow at Claremont, urged readers to “give up on the idea that ‘conservatives’ have anything useful to say,” and called for “all hands on deck as we enter the counterrevolutionary moment,” while asserting that the 80 million Americans who voted for Joe Biden were “not Americans in any meaningful sense of the term.”

In Trump, Claremont saw both an affinity and an opening. “It’s a little bit like the guy who runs and gets in front of the parade,” Tom Merrill, a political theorist at American University who has written about Claremont, said. “Was he leading it? Or is he just somehow channeling it?” Klingenstein told me that when Trump began to run for office in 2015, the board decided “that we were going to become a little more ‘small-p’ political, in addition to the philosophy.” The conservative movement “was less sure of itself,” Klingenstein said, and was in “a period of flux.” He went on: “We thought, We have a real opportunity now to put our philosophy into practice, so to speak. To apply it to the moment.”

Thomas Klingenstein, the chairman of the board at the Claremont Institute.Credit…Natalie Ivis for The New York Times

The Claremont Institute’s headquarters sit in an office park just outside the town of Claremont, 35 miles east of Los Angeles, in the dusky foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains. A Roman-style fountain stands in front of the entrance, and inside, a spiral staircase curls upward beneath an immense chandelier, suggesting a kind of European pastiche pushing back against the California wilderness. Much of the scholarly work at the Claremont Institute stems from the belief that the American founding is the culmination of centuries of Western political thought. But, thanks to a century of liberalism, the principle of self-governance has been replaced with a permanent class of unelected experts: the regulatory bureaucracy otherwise known as the administrative state. Members of Claremont wish to see the right take control of all three branches of government for a generation, dissolve certain federal agencies — break up the C.I.A., get rid of the Department of Education, shrink the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission — and also stop, as Anton wrote in “Flight 93,” the “ceaseless importation of Third World foreigners with no tradition of, taste for or experience in liberty.”

When Trump entered the 2016 presidential race, Claremont scholars were primed to see in him something that others did not. “We all believed and had been saying for a while that it almost doesn’t matter what Republican you nominate,” Anton told me. “On all the ways that the regime operates differently than what it’s supposed to, they’re going to agree and keep that going.” John Marini, a professor of political science at the University of Nevada, Reno, and a Claremont senior fellow, was one of the colleagues who got Anton thinking about Trump as a corrective to a system run amok. In 2015, Anton recalls, Marini began sending long emails to his colleagues arguing that Trump, in his unscholarly way, might have the potential to force the constitutional order back into its proper limits. In December of that year, William Voegeli, a senior editor of The Claremont Review of Books, the highbrow quarterly journal that has been the public face of the Claremont Institute for the last 22 years, published one of the first “anti-anti-Trump” essays, asserting what would become a guiding argument: “that such a flawed contender could be a front-runner tells us more about what’s wrong with the country than about what’s wrong with his followers.”

Key Revelations From the Jan. 6 Hearings

Making a case against Trump. The House committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack is laying out a comprehensive narrative of President Donald J. Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election. Here are the main themes that have emerged so far from eight public hearings:

An unsettling narrative. During the first hearing, the committee described in vivid detail what it characterized as an attempted coup orchestrated by the former president that culminated in the assault on the Capitol. At the heart of the gripping story were three main players: Mr. Trump, the Proud Boys and a Capitol Police officer.

Creating election lies. In its second hearing, the panel showed how Mr. Trump ignored aides and advisers as he declared victory prematurely and relentlessly pressed claims of fraud he was told were wrong. “He’s become detached from reality if he really believes this stuff,” William P. Barr, the former attorney general, said of Mr. Trump during a videotaped interview.

Pressuring Pence. Mr. Trump continued pressuring Vice President Mike Pence to go along with a plan to overturn his loss even after he was told it was illegal, according to testimony laid out by the panel during the third hearing. The committee showed how Mr. Trump’s actions led his supporters to storm the Capitol, sending Mr. Pence fleeing for his life.

Fake elector plan. The committee used its fourth hearing to detail how Mr. Trump was personally involved in a scheme to put forward fake electors. The panel also presented fresh details on how the former president leaned on state officials to invalidate his defeat, opening them up to violent threats when they refused.

Strong arming the Justice Dept. During the fifth hearing, the panel explored Mr. Trump’s wide-ranging and relentless scheme to misuse the Justice Department to keep himself in power. The panel also presented evidence that at least half a dozen Republican members of Congress sought pre-emptive pardons.

The surprise hearing. Cassidy Hutchinson, a former White House aide, delivered explosive testimony during the panel’s sixth session, saying that the president knew the crowd on Jan. 6 was armed, but wanted to loosen security. She also painted Mark Meadows, the White House chief of staff, as disengaged and unwilling to act as rioters approached the Capitol.

Planning a march. Mr. Trump planned to lead a march to the Capitol on Jan. 6 but wanted it to look spontaneous, the committee revealed during its seventh hearing. Representative Liz Cheney also said that Mr. Trump had reached out to a witness in the panel’s investigation, and that the committee had informed the Justice Department of the approach.

A “complete dereliction” of duty. In the final public hearing of the summer, the panel accused the former president of dereliction of duty for failing to act to stop the Capitol assault. The committee documented how, over 187 minutes, Mr. Trump had ignored pleas to call off the mob and then refused to say the election was over even a day after the attack.

“Flight 93” picked up on these arguments. Anton, who later served as deputy national security adviser for strategic communications, believed that Trump had staked out the correct, more nationalist positions on the three issues — immigration, trade and war — that would be critical to the right going forward. But it wasn’t just Trump’s positions that were of interest; it was also his “smashmouth style” that was indispensable. Anton told me that “in many millions of voters’ minds, those highly decorous political types, they saw them as timid and weak and not sufficient to the challenge.”

Charles R. Kesler, a senior fellow who edits The Claremont Review, declined to publish “Flight 93” in the print edition. But it was posted on the review’s website. Rush Limbaugh picked it up and read from it aloud on his radio show, sending readers by the hundreds of thousands to the review’s site, the only time an article caused it to crash.

A younger generation of leadership at Claremont seemed to recognize an online appetite for this style of polemic. A year later, Ryan Williams became president of the Claremont Institute. His predecessor, Michael Pack, left at the start of the Trump administration to lead the U.S. Agency for Global Media, which runs American-backed media outlets abroad. (Pack promptly dismissed executives of four of those networks, dissolved the boards and replaced many with Trump appointees.) Pack, at the time, was 63. Williams was 35. He hired a cohort of younger staff members, many of them also in their mid-30s, and embarked on a series of new projects, including The American Mind.

“I call it a kind of punk-rock C.R.B.,” Williams said when I met him in mid-February in a wood-paneled conference room at the institute, furnished with dark leather chairs and tableaux of the American founders. Williams is courteous but concise. He wore a tweedy wool jacket. “We wanted to speak to a younger audience, to try to understand and influence the New Right in its varied factions” — encompassing everything from the hard right to national conservatives — “and cultivate that audience for the better,” he added.

Williams also opened a new center in Washington, a first for Claremont, which had always been California-centric, called the Center for the American Way of Life. Just across the lawn from the Capitol, the new office is focused on fighting what its members see as the march of “wokeism” through American institutions. “A great deal of money is funneled into higher ed, and broadly speaking that money is a system of fraud,” Arthur Milikh, the executive director of the new center, told me.” He said that “decent Middle America citizens” pay taxes to support universities that are teaching “young people to despise their country or at least have no duties to it, be indifferent to it.” He went on: “And all of this is being done at the expense of the public. So I think that states need to start defunding higher ed. Giving it less and less money. And that’s something that we’ve had some initial successes with.” In 2021, for example, the center, working with the Idaho Freedom Foundation, wrote reports detailing how “social-justice ideology” had penetrated Idaho’s universities. The Idaho Legislature cut $2.5 million from funding for social-justice programming at public universities and banned public educational institutions from directing “students to personally affirm, adopt or adhere” to tenets associated with critical race theory. (Critics have warned that such laws may violate the First Amendment and could have a chilling effect in classrooms.)

At American Mind, the online magazine, Williams has taken the traditional Claremont shibboleth of the “ruling class” and joined it to what he sees as the new zeitgeist of “wokeism,” arguing that to “defend America,” they must “defeat multiculturalism,” including what Klingenstein, the chairman of Claremont’s board, calls “woke communism.” In recent decades, Williams told me, the administrative state has been put to use in new ways, i.e. the “expert administration of social justice, for lack of a better term.” A week before we met, he said, a group of Democrats in the House introduced a bill providing for “the establishment of a Cabinet-level Department of Reconciliation charged with eliminating racism and invidious discrimination,” which echoed the ideas of the antiracism scholar Ibram X. Kendi. Williams allowed that such a bill stood no chance of passing. But, he said, “vanguard movements can be 8 or 10 percent of a political movement and yet drive the agenda. Part of our job here has always been to try to see down the road at the threats coming, and especially challenges to constitutionalism as we understand it.”

Claremont, he said, saw itself as championing individual rights, not a never-ending succession of demands for new special classes — based on race, gender identity and sexual orientation — for which the 1964 Civil Rights Act laid the foundation. He cited an argument put forward in “The Age of Entitlement,” a 2020 book by Christopher Caldwell, a senior fellow at Claremont: “Whatever was meant by the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and it had a very noble purpose, which was to overcome and fix the problems of Jim Crow and segregation, it quickly got taken up by the courts and administrative agencies, not in the fulfillment of the promise of the colorblind Constitution or the Declaration of Independence, which is how we read it — equal protection for all regardless of skin color or position.” Instead, he continued, a new “racialized, hierarchical politics” had installed itself “where the formerly oppressed are now given privileges and power and the former oppressors are brought low.”

Claremonters like to refer to a lecture by the storied German American philosopher Leo Strauss, who fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s, in which he argued that German intellectuals failed to take seriously and guide a generation of young men who rejected the new social order of interwar Germany, leaving them open to Nazism. When Williams took over at Claremont, he became “very interested in harnessing some of the energy that he saw among young people who were being drawn to the alt-right or to nonmovement forms of rightism,” Matthew Continetti, the author of “The Right,” a new history of American conservatism, who was a Lincoln fellow at Claremont, said. “He began widening the scope of the people that were being admitted to the educational programs and incorporating people like Curtis Yarvin” — a neo-reactionary blogger who has become a guru to the ill-defined “New Right” for his anti-liberal screeds — “into the roster of contributors to The American Mind.” Nate Hochman, a 24-year-old fellow at National Review, told me that the editors of American Mind were “the only ones that were willing to actually reach into the goo of the fever swamp of young right-wing internet circles” and “parse the completely crazy stuff from the understandable, or verging on legitimate stuff, and extend a hand and be like, Come with us instead. No other conservative institution was willing to do that.”

In 2019, Anton, charged with writing an essay for The Claremont Review on the “alt-right,” chose as his subject the work of an anonymous, supposedly Yale-educated theorist going under the name Bronze Age Pervert, whose book, “Bronze Age Mindset,” was popular with young people. In a style that mixed a kind of faux-caveman brutishness and message-board pidgin with classical references, Bronze Age Pervert informed his readers that “you don’t see yourself as you really are” because “spiritually your insides are all wet, and there’s a huge hole through where monstrous powers are [expletive] your brain, letting loose all your life powers of focus.” Channeling a pseudo Nietzschean critique of modernity, Bronze Age Pervert argued that all life-forms naturally yearn to master space and, as Anton summarized, “today all the space is, and has been for some time, ‘owned’ by a degraded elite, reducing the majority of men to ‘bugmen’ and thwarting the innate will of the higher specimens.”

The book, Anton wrote, was significant because it spoke directly “to a youthful dissatisfaction (especially among white males) with equality as propagandized and imposed in our day: a hectoring, vindictive, resentful, leveling, hypocritical equality that punishes excellence and publicly denies all difference while at the same time elevating and enriching a decadent, incompetent and corrupt elite.” Bronze Age Pervert regarded the founders’ idea of rights, the very bedrock of the American political tradition, as false. This mattered, Anton said, because “all our earnest explanations of the true meaning of equality, how it comports with nature, how it can answer their dissatisfactions, and how it’s been corrupted — none of that has made a dent.” Conservatives didn’t have to agree with any of this, but they did need to acknowledge that “in the spiritual war for the hearts and minds of the disaffected youth on the right, conservatism is losing. BAPism is winning.”

Anton’s essay provoked some fiery reactions on the right, responses that ran in The American Mind. One argued that “rather quite tragically, Michael Anton is the super carrier who brought the virus of the reactionary Right into the bloodstream of the conservative intellectual movement.” Continetti told me that “younger conservatives who are drawn to national conservatism or national populism, The American Mind is what they’re reading and quoting.” At the same time, The Claremont Review and The American Mind were “taking a dual-track approach,” he said. “The most controversial things associated with Claremont don’t appear in the magazine’s pages,” Continetti said, “but it exists in this kind of relationship where Anton will appear in its pages and also write the spicy stuff for the online outlet.”

Hochman, who participated in Claremont’s Publius fellowship last year, told me that “it was attractive to have people who were speaking about the contemporary moment in terms that felt much more familiar to me.” Younger conservatives had the sense, he said, that the kind of activism they’d encountered on liberal campuses was “seeping out into every other institution in American life.” Among conservative institutions, Claremont was alone in “articulating a sense that we are in a kind of cold civil war.” It wasn’t just disagreement over marginal tax rates, Hochman said, but “literally just the things we do together in a shared community — universities, the arts, Hollywood, academic orthodoxy, the media.” Hochman said that many of his peers who read Bronze Age Pervert “ended up reading Anton’s review of it, and then ended up doing Publius.” It’s not that they took Bronze Age Pervert’s philosophy completely seriously, he said, but “why did every junior staffer in the Trump administration read ‘Bronze Age Mindset?’ There was something there that was clearly attractive to young conservative elites.”

If a single figure can be said to serve as the intellectual foundation for the Claremont Institute, it is the conservative political philosopher Harry V. Jaffa. It was Jaffa who crafted the famous couplet for Barry Goldwater’s acceptance speech at the 1964 Republican convention: “I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. And let me remind you also that moderation in pursuit of justice is no virtue.”

Born into a New York Jewish family, Jaffa studied at the New School for Social Research with Leo Strauss. When Strauss arrived in the United States in the late 30s, he found American democracy to be shallow and materialistic, concerned only with economic prosperity and protecting capitalism. With his students, he implemented a regimen of classics, teaching Plato and Aristotle, hoping to awaken in them a reverence for virtue and the nobility of human achievement. One day, while still a graduate student, Jaffa was browsing in a used bookshop in Manhattan when he came across a copy of the Lincoln-Douglas debates on slavery. Flipping through the series of 1858 exchanges between Abraham Lincoln, then the challenger for the U.S. Senate seat from Illinois, and Stephen Douglas, the incumbent, Jaffa discovered a 19th-century American rendition of Plato’s dialogue on the nature of justice. “I realized that the issue between Lincoln and Douglas was identical to the issue between Socrates and Thrasymachus,” Jaffa later wrote. “Not similar to it. Identical.” Douglas took a relativist position: in a free, self-governing society, the majority decides what is right, and citizens should determine for themselves whether slavery should be extended into the new American territories. Lincoln vigorously disagreed, affirming the existence of universal truths, that all men are created equal and that certain moral principles are immutable.

Building on Strauss, Jaffa argued that the Declaration of Independence drew upon both the classical philosophical concept of objective or natural right and the Christian moral teaching of individual equality. America was the confluence of Athens and Jerusalem, the first time in human history that reason and revelation together formed the foundations of a political community. There was a profound contradiction, however, in the persistence of slavery. It was not until Lincoln, the philosopher-statesman and savior of the republic, that America achieved what Jaffa called “the best regime.”

Jaffa’s 1959 book, “Crisis of the House Divided,” is regarded by academics across the political spectrum as both a groundbreaking contribution to Lincoln scholarship and a thoroughly engrossing piece of writing. In the 1960s, he caught the attention of Henry Salvatori, a wealthy California oil surveyor who later became part of Ronald Reagan’s kitchen cabinet. He was recruited to teach at Claremont Graduate School and Claremont Men’s College, which was founded in 1946 for returning G.I.s as part of a consortium of schools that started with Pomona College just down the block. Jaffa was an incandescent figure at Claremont, drawing a small but significant cadre of devoted graduate students, who became known as the “West Coast Straussians.” If the “East Coast Straussians” accepted that the American founding was “low but solid,” as the students themselves liked to say, lacking a driving ideology but enabling the pursuit of the good life, the West Coast faction held to a fervent belief in America as the culmination of Western civilization.

Jaffa was an influential teacher, sometimes called a “pied piper,” but he had a reputation for being cantankerous and pugnacious, even with friends. He was a consistent presence in the pages of the little-magazine ecosystem of the conservative intelligentsia and was especially keen on picking fights with other conservative intellectuals. William F. Buckley Jr. once wrote, “If you think Harry Jaffa is hard to argue with, try agreeing with him.” In 1988, Jaffa turned 70, which was, at the time, the mandatory retirement age, but he commandeered an area in the basement of the Claremont colleges’ library, where he continued to hold forth, giving informal seminars for the next decade.

A group of Jaffa’s doctoral students, wanting to share their ideas with a wider public, set up a rickety little organization in 1978 called Public Research, Syndicated. From an office building near campus, they wrote opinion essays and mailed them out to local newspapers across the country. The students, Larry Arnn, Peter Schramm, Tom Silver and Chris Flannery, established the Claremont Institute in 1979, and Public Research, Syndicated faded after a few years. (The Claremont Institute is not affiliated with the schools.) It was the end of the Carter administration, after the catastrophe of the Vietnam War and the rise of stagflation. “The reigning authoritative, almost impregnable opinion was that nothing is by nature right or wrong,” Flannery told me. “And we all became persuaded by our studies that that view was radically inadequate. It disabled you from dealing with human affairs as they deserved to be dealt with.” They started the Publius fellowship, which soon developed into a six-week graduate-style summer seminar. Charles Kesler, who read Jaffa’s “Crisis of the House Divided” as a student at Harvard, was among the first Publius fellows, in the summer of 1980.

In the 1970s, Washington think tanks were coming into being as an institutional sector — the Heritage, Cato and Manhattan institutes were all founded around that time. Away from the D.C. establishment, Claremont sought to distinguish itself from the others. “Claremont has always been proud to call itself patriotic,” Ellmers, the Claremont senior fellow, told me. “But it also offers a principled explanation of what that patriotism means, and has to mean, to actually be worthy of our admiration. Why is it good to be an American patriot? What does it mean? What is it about America that’s worth loving? You don’t get that from a lot of the places that churn out policy papers in D.C.”

Claremont was rooted in the plucky outsider, swashbuckling frontier conservatism of California, which shaped its perception of America. Anton grew up in Northern California and has compared the California of his youth to the “golden times” of Rome, describing it as “the greatest middle-class paradise in the history of mankind.” That California, however, was “swept away” in “barely one generation,” Anton wrote in his 2020 book “The Stakes: America at the Point of No Return” and “transformed into a left-liberal one-party state.” In the hands of misguided incompetents — “the ruling class” as the late Claremont scholar Angelo M. Codevilla called it — California had become “the most economically unequal and socially divided” state in the country controlled by “oligarchic power concentrated in a handful of industries, above all Big Tech and Big Hollywood.”

One of Claremont’s founders, Peter Schramm, served in Reagan’s Department of Education. In the late 1980s, Clarence Thomas, as chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission under Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, was on the defensive as a Black conservative and looking for people who could help him sharpen his worldview. He hired as his aides the Claremont scholars Ken Masugi and John Marini, who would later be among the first to make the case for Trump. They were theorists who “understood Lincoln,” as Thomas described them. In a period that Thomas was later to recall as one of “great intellectual development,” they spent hours discussing Jaffa’s teachings on natural law and an interpretation of the Constitution, based on the principles of the Declaration of Independence, which Thomas began to cite.

Convinced by Lincoln’s argument that “public sentiment is everything,” Claremont was devoted primarily to shaping opinions. “The most successful thing that the Claremont Institute has done is this educational effort,” Continetti told me. “Trump did fill his administration, maybe not with Claremont personnel, but with Claremont alumni.” People left the fellowship program with a heady narrative of America to contemplate and a cluster of like-minded friends and future colleagues: the Arkansas senator Tom Cotton; the Newsweek opinion editor Josh Hammer; the right-wing activist Christopher Rufo; the pundit Ben Shapiro; the far-right influencer (and propagator of the “Pizzagate” conspiracy theory) Jack Posobiec; and Babs Hough, a former staff member for Representative Marjorie Taylor Green of Georgia, have all participated in Claremont fellowships. Anton, who now teaches at the Washington branch of Hillsdale College, the conservative Christian school in Michigan, was not the only one to say that it had changed his life.

Rufo, who has led several recent campaigns against critical race theory and school curriculums on “gender ideology,” did a Lincoln fellowship in 2017. He told me that Claremont is a “brotherhood” of the sort that has largely vanished from American life, “all of these places where people, and predominantly men, could get together, talk about important social and political issues, look at and investigate philosophical ideas and then chart a practical way forward.” The experience, he said, “put my life and my politics into sharp focus.” A central insight from Claremont is that “the man of action is someone to be admired. And it’s a kind of virtue to take things from the realm of ideas to the realm of action,” Rufo said. “And what I’ve been able to do is exactly that.”

Kesler, the editor of The Claremont Review of Books, is widely regarded, at 65, as the institute’s éminence grise. Unfailingly congenial, he was walking beside his cat beneath a long white portico in front of his house in Pasadena when I pulled up one morning in February. The house, in a pristinely kept neighborhood, was in the Spanish Revival style. Inside, a similar Old World flourish prevailed: deep regal reds and blues, floral-patterned French-country upholstery, highly stylized rococo furniture. Brimming bookshelves lined the garage.

To an extent, Kesler represents an old guard at Claremont. Most of the other Claremont Institute scholars did their work at Claremont Graduate University, but Kesler was completing his Ph.D. at Harvard when he arrived at Claremont McKenna College (formerly Claremont Men’s College) only at the beginning of his teaching career, in 1983. Growing up in West Virginia in the late 1960s, Kesler used to watch William F. Buckley Jr. on “Firing Line” on PBS. “I became fascinated by Buckley,” Kelser told me. “There was nobody like him, then or now.” He managed to interview Buckley for his high school newspaper, an encounter that led to a lifelong friendship and mentorship. (Buckley wrote his recommendation for Harvard.) Inspired by the kind of influence that Buckley’s National Review wielded in American postwar conservatism, Kesler became the editor of The Claremont Review of Books in 2000, which flourished under his leadership as one of the most reputed cultural and literary publications of the American right, read by intellectuals, think-tank members, Republicans on Capitol Hill and anyone interested in the state of conservative thought. Its pages are filled with meditations on Aristotle and Locke, Jefferson and Hamilton, Huntington and Buckley. “It’s our attempt to reach our fellow Americans directly and to pitch our arguments to them,” Kesler told me, “trying to connect with them on issues urgent and immediate, but also lasting and eternal.”

Through the George W. Bush years, Kesler and others at Claremont voiced their opposition to the Bush consensus on foreign policy. With their beliefs in the historical and cultural processes necessary to bring about self-governance, they were critical of the administration’s contention that it could swiftly set up democracy in Iraq. This was why, in large part, they were equally against Bush’s immigration reforms.

Kesler was especially devoted to theorizing about what he saw as the menace of progressivism. As he wrote in his 2021 book, “Crisis of the Two Constitutions,” the takeover of the country by the “administrative state” marked a fundamental change in the understanding of the purposes of government and was “based on a new view of the nature of man.” The figure who “prepared this revolution” was Woodrow Wilson, who served as president from 1913 to 1921. Though the framers had constructed a government “to display the laws of nature,” Wilson argued that the laws of nature were antithetical to human freedom. Because history is progressive, each new generation might find that the definitions of liberty and happiness, and therefore the appropriate forms of government, would change as well. In Kesler’s reading of Wilson, the Declaration of Independence could “therefore have no teaching concerning the best regime or even ranking legitimate regimes,” putting the country into a chaotic and potentially disastrous tangle of relativism.

Kesler’s critique dovetailed with a wider Republican antagonism to a liberal administrative state, but Kesler and the others at Claremont went further, seeing this “fourth branch” as overturning the Constitution. Madison, Hamilton, Jay and Jefferson, he contended, would hardly recognize America today.

Despite some reservations about Trump’s character, Kesler saw in him some of the same corrective possibilities and opportunities for influence as others at Claremont did and urged conservatives to support Trump in 2016, predicting that he would win the Republican nomination. He was also hospitable to some of the Trump administration’s positions and initiatives. In May 2019, the Claremont Institute held a 40th-anniversary gala, at which it honored Mike Pompeo, the secretary of state, with its statesmanship award for “manning the battlements of Western civilization.” In September 2020, Kesler was appointed to the 1776 Commission, which Trump created after a summer of mass demonstrations following the police killing of George Floyd. Trump named Larry Arnn, a founder of the Claremont Institute, now president of Hillsdale College in Michigan, chairman of the commission. Kesler called the sometimes-violent protests “the 1619 riots,” after the 1619 Project, published in this magazine, a series of articles that sought to reframe the American founding as defined by slavery. The 1776 Commission released a hastily written report, conceived as a response to the 1619 Project, with the aim of enabling “a rising generation to understand the history and principles of the founding of the United States.” It was filled with Claremont ideas.

The view that America’s founding principles are being fatally undermined by progressives seems to be at the root of what Kesler and others at Claremont find so disastrous in the presidency of Joe Biden. Kesler does not participate in some of the more bellicose performances of his colleagues and did not attend a recent panel discussion they organized titled “The Lies of the Ruling Class.” (He told me that he disagreed with how Ellmers, the Claremont senior fellow, had characterized Biden voters as “non-Americans” and told him so.) But he shares in the moral battle they see at the heart of today’s conflict. “In some ways,” he said, “the worst thing about Biden to me is precisely his embrace of the left-wing part of the Democratic Party’s moral critique of America,” Kesler said. “That it’s a racist country, in its DNA, that it has always been basically unjust, that it’s been a kind of petty tyranny, intellectually, morally and spiritually, and it has never really risen above the crassest kind of self-interest, whether along class lines or racial lines or any lines of possible oppression.”

When I met Kesler, it was several months after the public revelation of the memos that John Eastman drafted containing the scenarios he outlined for Mike Pence. The latest issue of The Claremont Review of Books had just come out, featuring an exchange over the memos between Eastman, who defended them, and a Claremont McKenna College professor named Joseph Bessette, who offered a stinging critique. After Jan. 6, Eastman reached an agreement to retire immediately from the professorship he held at Chapman University, in Orange, Calif., but Claremont kept him on. When I asked Williams, the president of the Claremont Institute, about that decision, he told me, “We’re not going to throw him under the bus just because his representation of the president was controversial.” Klingenstein struck a similar note, telling me that Eastman is “one of ours” and a friend, while adding that their support was “not exactly a defense” of his advice to Trump.

Of the debate between Eastman and Bessette, Kessler said: “I thought both of them gave the best version of the case I’d read or thought of from either side. I disagree with John. I think it was a bad idea to give Trump that advice and an even worse idea to speak at the rally.” (Eastman addressed the crowd of Trump supporters at the Ellipse on the morning of Jan. 6.) But the question for the review, he said, was, “What are constitutionalists to think about the advice that was given and what happened on Jan. 6? And I’ve tried to make it crystal clear that constitutionalists should be aghast at what happened on Jan. 6, and there should be no pooh-poohing of it, no snide diminution of it. It was a very open, brazenly wrong thing, without it amounting exactly to a coup, I think that’s going too far. But still, it was a riot, and who knows what would have happened.”

Others at Claremont were more willing to see Eastman and those who marched on the Capitol as acting out of a principled conviction that the election was fatally flawed. Williams told me that he was bothered by the “rampant unconstitutional processes” in which the election was conducted — like the expansion of mail-in balloting — and what he claimed was the “media blackout on any negative stories about Biden.” Anton concurred, citing, in Compact, a new right-wing magazine, what he saw as the lack of enforcement of voter-ID laws and the abrupt cessation of late-night vote counting. (There is no evidence of electoral irregularities sufficient to change the outcome of the election.) “To all of these and many other questions and doubts,” he wrote, “the ruling class has but one response: Shut up, white supremacist. Questions aren’t allowed, investigations won’t happen and explanations won’t be given.”

There was a divide at Claremont over the response to Eastman that reverberated through the wider conservative world. Chris Flannery, one of Claremont’s founders, called Eastman “an American hero.” Continetti stopped contributing to The Claremont Review. For his part, Kesler doesn’t accept Trump’s claims of election fraud. “I’ve always thought that Trump lost,” he said. “Trump won a close election four years ago, he lost a close election, not quite as close but still a fairly close election this time, and you don’t need any vast conspiracy to explain what happened, because what happened was just a normal part of American politics.” If he believed that to be the case, I asked, then wouldn’t running a serious appraisal of Eastman’s legal analysis be opening a Pandora’s box? “No, no, I think it’s shutting the Pandora’s box really,” Kesler replied. “In the sense that, I think, the Pandora’s box was opened already.”

Harry Jaffa died in January 2015, at 96, and didn’t live to witness the rise of Donald Trump. An emotional debate has ensued as to how Jaffa, who continued to write and argue well into his 80s, might have reacted to the events of the last few years. This spring, one of Jaffa’s sons, Philip, who is 70, emailed me. He is adamant that the Claremont Institute has turned against his father’s teachings. He cited an essay by Christopher Caldwell about Robert E. Lee that The Claremont Review ran last spring, which called Lee the “moral force of half the nation.” Philip noted that this directly contradicted his father’s teachings. “I have come to watch the Claremont Institute embody the very things that my father criticized in the conservative movement,” Philip Jaffa told me when I spoke with him.

Some of the most pointed criticisms of Claremont’s recent prominence have come from scholars with similar backgrounds. “I think there’s a story here about the insularity of the conservative world,” says Laura Field, a political philosopher and scholar in residence at American University, who has published several sharp critiques of Claremont over the last year in The Bulwark, a publication started by “Never Trump” conservatives. Claremont has been “pretty much unchallenged by broader academia,” Field told me, as many academics, liberals but also other conservatives, tend to consider political engagement in general, and Claremont’s ideas and public manners in particular, beneath them. In contrast, Claremont scholars “understand the power of a certain kind of approach to politics that’s sensational,” she said. Field pointed me to a recent exception, a small panel discussion in July, in Washington, in which Kesler took part. Kesler defended the upsurge of populism as “pro-constitutional,” and so, he said, “even though it takes an angry form in many cases,” it was difficult to “condemn it simply as an eruption of democratic irrationalism.” Bryan Garsten, a political scientist at Yale, responded that it was very generous to interpret the current populism as “erupting in favor of an older understanding of constitutionalism,” but even if that was partly true, he questioned whether populism could “be expected to generate a new appreciation for constitutionalism” or whether it wouldn’t “do just the reverse.” It is, Garsten said, “a dangerous game to try to ride the tiger.”

Nonetheless, Claremont’s recent successes have made for effective fund-raising. Klingenstein, Claremont’s chairman, who runs a New York investment firm, was, as recently as 2019, Claremont’s largest donor, providing $2.5 million, around half its budget at the time. Claremont’s budget is now around $9 million, and Klingenstein is no longer providing a majority of the funding. “They’re increasingly less reliant on me, and that’s a good thing,” Klingenstein said. (On Steve Bannon’s “War Room” podcast on July 15, he noted that the budget kept going up.) Other big recent donors, according to documents obtained by Rolling Stone, include the Dick and Betsy DeVos Foundation and the Bradley Foundation, two of the most prominent conservative family foundations in the country.

Many Claremont scholars are still supportive of Trump but have also cultivated relationships with other figures of potential future importance, especially Ron DeSantis, perhaps envisioning a day when Trumpist conservatives find a more dependable and effective leader. Arnn, the president of Hillsdale College, which has many Claremont graduates on its faculty and a robust presence in Washington, conducted an event with DeSantis last February at which he called DeSantis “one of the most important people living.” According to The Tampa Bay Times, Hillsdale has helped DeSantis with his efforts to reshape the Florida education system, participating in textbook reviews and a reform of the state’s civics-education standards. But Claremonters are not entirely willing to cast Trump aside. “Trump is loved by a lot of Americans,” Kesler told me, “and you’re not going to succeed in repudiating him and hold the party together, hold the movement together, and win.” He said that the future lay “probably with Trumpism, some version of Trump and his agenda, but not necessarily with Trump himself. And that’s because I don’t know that he could win.” The argument in 2016 was, “We’re taking a chance on this guy, we’re taking a flyer,” Kesler said. “And I just don’t think they’re willing to take a second flyer.”

Harry Jaffa used to ask what it was that American conservatism was conserving. The answer was generally ideological — American conservatism was not about preserving a social structure, as in the old European societies, but rather the American idea, a set of principles laid out in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. What appears unsettled at Claremont is “the foggy question of whether or not a republic is too far gone to be conserved,” William Voegeli, the senior editor, wrote in the spring issue. “Which would be the bigger mistake — to keep fighting to preserve a republic that turns out to be beyond resuscitation or to give up defending one whose vigor might yet be restored?” Voegeli, at 67, comes down on the side of the “central conservative impulse,” which is that “because valuable things are easy to break but hard to replace, every effort should be made to conserve them while they can be conserved.” But he acknowledges that some of his younger colleagues appear ready to “abandon conservatism for counterrevolution,” in order to “re-establish America’s founding principles.” Kesler was sanguine. “We need a kind of revival of the spirit of constitutionalism, which will then have to be fought out, through laws and lawsuits and all the normal daily give and take of politics,” he said. “That’s what I’m in favor of. And it’s moving in the right direction.”

Tom Merrill, of American University, also studied Jaffa’s work and believes there is much in his teachings to appeal to both liberals and conservatives. “I think the country is so divided right now that if you had a Republican candidate who was like, ‘You know, we messed up in a bunch of ways but we’re mostly pretty good,’ I think that there would be a big middle lane, and it would defuse some of this anger.” The American right at present, Merrill argued, was in need of guidance and leadership that could not come from the traditional establishment, which voters had rejected. “There is a movement out there that isn’t the Republican Party, that needs people to speak for and sort of shape the message,” he said. In the past, that had meant movement conservatives cordoning off the undemocratic, un-American elements on the far right. Claremont could have filled that role, he argued, but “the central challenge facing the right is, Can someone take those themes and articulate them in a grown-up way?”

Some at Claremont have expressed a desire to work with liberals, yet their strategy seems to suggest the opposite. When I asked Williams what Claremont’s ideal future would look like, he cited the deconstruction of the administrative state. He told me recently that the June Supreme Court ruling constraining the E.P.A. is “a step in the right direction,” and he would like to see “Congress get back into the act of legislating” instead of delegating rule making to bureaucracy, a “long-term and complicated process involving legislators learning rules that they haven’t used in 30 years.” Prudence, he added, dictated that change should be incremental. “Though I can anticipate your next question, which is, You guys talk like counterrevolutionaries,” Williams said. “One of the goals of the more polemical stuff is to wake up our fellow conservatives.”

Klingenstein took a starker view. “If it’s true that the country is as divided as we think it is, and if the situation is as dire,” he said, “it’s very important for conservatives to understand this. Because if you’re actually in a war, even if it’s a cold war, you behave differently. You’re less inclined to compromise. You’re more aggressive. In war, you don’t negotiate until you’ve won.”

Elisabeth Zerofsky is a contributing writer for the magazine who has reported across Europe. Her last feature was on the rising nationalistic faction on the French far right.