The Artist and Mystic Who Collected the World

COSMIC SCHOLAR: The Life and Times of Harry Smith, by John Szwed

Two pages into his new biography of Harry Smith, the enigmatic anthropologist, underground filmmaker, painter and music collector responsible for the influential “Anthology of American Folk Music,” John Szwed sends up a flare of distress. “How did I get here?” he writes. “Who is Harry Smith? Why am I writing this book?”

His unease is understandable. Smith (1923-91) is a hard moth to pin to the specimen board. Facts about his life, especially his early life, are hard to come by. The occupations I provided above aren’t the half of it. Smith had his fingers in a thousand pies, the more occult and arcane the better.

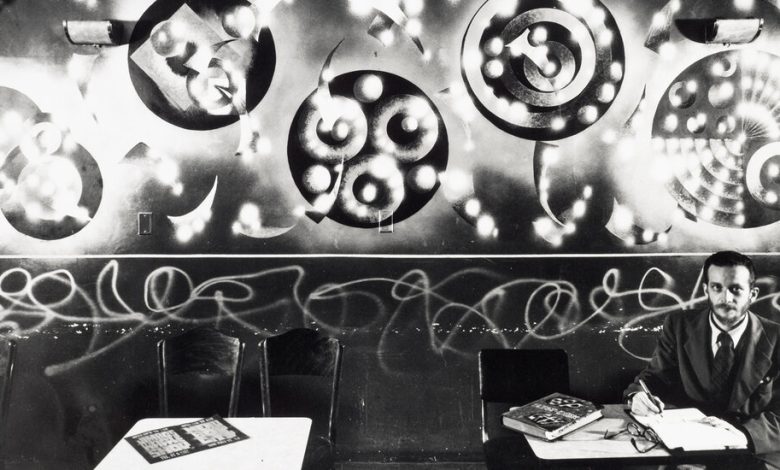

He was one of the great downtown New York figures of the second half of the 20th century. Scraggly, stooped, wild-haired, impeccable in his sloppiness, he was a knowingly inverted dandy, as Walker Evans once said of James Agee. (Smith looked like Evans, if you crossed him with a billy goat.) He lived for years in the Chelsea Hotel and befriended Patti Smith.

His tiny apartments, sometimes in flophouses, were infamous. He dwelled, up to his gonads, in apparent junk. To him, the detritus was precious. He collected paper airplanes (there is a terrific book of these); string figures; bandages peeled off fresh tattoos, imprinted with bloody mirror images that he considered more interesting than the tattoos themselves; frozen dead birds; crushed cans; and, Szwed writes, “the recorded death coughs of bums.” He searched for patterns, the connections between things. He wandered the world as if it were his personal shoreline. Smith was an ambassador from the territory Greil Marcus has delineated as the “old, weird America.”

He was brilliant but caustic, devilish, often drunk and prone to rages. The bees that buzzed in his cranium would emerge to sting. He had bad teeth. He was seen to be, Szwed writes, “a bum, or a mendicant, panhandler, beggar, a schnorrer.” His brand of charisma was not for everyone. Yet Bob Dylan, Philip Glass, Leonard Cohen, Tennessee Williams, Allen Ginsberg and Jerry Garcia were among those drawn to him. Ginsberg and Garcia helped keep him afloat when the money ran out, as it often did. Smith never really had a job and when he came into any money it trickled right through his fingers.

Szwed’s book, “Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith,” is the first comprehensive biography of this hipster magus. It tours his life without ever quite penetrating it. But it’s a knowing and thoughtful book. Szwed, who has also written biographies of similarly protean figures such as Sun Ra, Alan Lomax and Miles Davis, is a perspicacious reporter. He wrestles this material into a loose but sturdy form, as if he were moving a futon. He allows different sides of Smith’s personality to catch blades of sun. He brings the right mixture of reverence and comic incredulity to his task.

Smith was born in Portland, Ore., and grew up in and around Washington’s Puget Sound. His father worked as a marine engineer in canneries. Harry had spinal problems from what might have been rickets. He was a short, thin, awkward, lonely, bookish boy with few friends.

He collected things like driftwood and animal skeletons. In high school, he developed an interest in local Native American tribes, including the Swinomish and Lummi. He was beloved by them for his “seriousness, persistence and humility,”Szwed writes. With their permission, he took photographs and made recordings and drawings.

Smith graduated from high school in 1943 and got a medical exemption from the draft. He refused to let college get in the way of his education. He briefly studied anthropology at the University of Washington, and worked nights as an engine degreaser in a Boeing factory before moving to San Francisco. There Smith moved in a wide range of circles. He made films and painted, and was funded by the Guggenheim Foundation. He befriended Thelonious Monk and Charles Mingus.

He was already a voracious collector of recorded music, as driven as the most butterfly-mad lepidopterist, everything from the blues and hillbilly music to every variety of world music. His version of a mixtape, “The Anthology of American Folk Music,” first appeared in 1952. It was a set of six LPs divided into three volumes, “Ballads,” “Social Music” and “Songs,” from white and African American musicians. All the songs were originally recorded between 1927 and 1932.

The set was expensive. It barely sold. It was a bootleg passion project (Smith lacked rights to albums that had been withdrawn from circulation), and was unavailable for years because of permissions issues. Yet it kept being rediscovered, and it became a crucial countercultural document. Before it came out, Szwed notes, people thought folk music was earnest and often mealy stuff like Burl Ives and the Weavers.

Americans began to search out the musicians on the records, people like Dock Boggs and Mississippi John Hurt, many of whom were still alive. Dylan alone, in Szwed’s estimation, has recorded his own versions of at least 15 of the set’s 84 tracks. “It was our Talmud,” the folk singer Dave Van Ronk said. “It was our Bible.”

Smith moved to New York City in 1951. His interests in topics like parapsychology, hieroglyphics, astrology and alchemy blossomed. He was a secular holy man, always trying to see through his third eye. He seemed to be tuned into a larger part of the electromagnetic spectrum.

He produced records by noted rabbis, learning Hebrew to do so, as well as the Fugs and Ginsberg. The screenings of his experimental films were legendary happenings. The avant-garde filmmaker Jonas Mekas was Smith’s great champion, and often wrote about him in his Village Voice column. In 1965, one headlined “The Magic Cinema of Harry Smith” declared him “the only serious film animator working today.”

Smith had major patrons, including Elizabeth Taylor. There were big parties, and messy scenes. He destroyed or threw away some of his own artwork during tantrums. Much of the rest was tossed out by landlords when he was behind on rent, or it was simply lost. In May 1964 he spent weeks plodding through the stench of Fresh Kills Landfill in Staten Island looking for his life’s work. Smith’s packing and moving days were such chaotic scenes that Robert Frank showed up to record one.

He had a gift for snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. Drink and drugs, which he used to soften the jagged edges of his mind, took a toll. He burned most of his bridges. He was a consumptive, self-eaten. Friends thought he lived on Skittles, pickled herring, NyQuil and capers. By the mid-1970s, he began to seem like a joke that 1958 bohemia had left behind.

Ginsberg, who was fed up with Smith festering in his apartment, ultimately moved him out to the Buddhist-inspired Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colo., where in the late 1980s he was given the title Shaman-in-Residence. He died back in New York, at the Chelsea Hotel, from bleeding ulcers and cardiac arrest.

Read this book with a YouTube tab open on your laptop, in addition to Spotify. There’s a lot of material to tap into, and you’ll want to. Smith added a great deal to the national stock of peculiarity. He was the worm at the bottom of American culture’s mezcal bottle. You slam the glass down, because his experience still makes you feel alive.

COSMIC SCHOLAR: The Life and Times of Harry Smith | By John Szwed | 404 pp. | Farrar, Straus & Giroux | $35