Mom’s in Rehab

It was January 2015, and all anyone could talk about was Ebola, Boko Haram, and Charlie Hebdo. I was 23, and I didn’t care about any of it. The world was ending? Of course the world was ending. My mom was gone. I was the one who sent her away.

For months, I had plotted against her — with her siblings and friends, with professional interventionists — until, while she sobbed and sobbed, I packed her suitcase. All I can say is: I was desperate. The woman I loved, in the doe-eyed way you can only ever love the one you imprint on, had been consumed by the parasitic brain worms of alcoholism. I was out of options.

Weeks passed. Her 30-day stay at the rehab facility in Minnesota turned into 60. Like a usurper, I left my small apartment in Manhattan and moved into her house — my childhood home in suburban New Jersey, unrecognizable with disrepair.

I brought my boyfriend, my dog and my M.F.A. homework. I commuted to my secretarial job in Midtown on New Jersey Transit and drove my youngest sister to her extracurriculars. I acted like everything was normal, all the while wondering what I had done.

Around Christmas, my mother stopped responding to my emails. If I wanted to talk to her, to convince her and myself that I had done the right thing, I would have to track her down in person. So I boarded a plane to Minnesota for “the Family Program.”

I met my middle sister, Emma, at the Hertz counter in the Minneapolis airport, where the clerk tacked on an underage fee for our Toyota Camry. At the Holiday Inn Express, we drank red wine out of paper cups on a queen bed. We didn’t talk about Mom or how things would go in the morning. We wanted her to be healed; we worried she wouldn’t be.

For weeks, we had been getting reports: She thinks she is special, different from the other patients. She thinks she doesn’t need to be here.

The thing I knew was: She was special. Always had been. Gorgeous and generous and warm. Bawdy and mischievous and charismatic. She made friends wherever she went and believed — against all evidence — that I could do the same.

Her nurses and counselors were less than charmed. In their notes, they implied that she was manipulative, hostile, uncooperative.

I knew that side, too. But I had blown up our lives on the promise that we could get her back — the real version — and I wasn’t willing to concede defeat until I saw her for myself.

The first day of the program, Emma and I left the hotel at 6 a.m. For four days, we wouldn’t see the sun. It was dark as I scraped ice from the windshield each morning and dark as the steering wheel slipped through my gloved grip on our drives back.

The facility itself was a hospital-bright contrast to the northern darkness. On the first day, Emma and I wore name tags as we listened to testimony and watched videos about addiction. We waited to see our mom, but the patients never came.

When I asked after her on the second day, a counselor reminded me to “focus on myself.” On the third day, I wanted to leave. I felt tricked by their brochures, so I turned myself into a platitude machine. When asked to name a higher power, I said something embarrassing about writing. A lie, dripping with treacle, that made everyone clap.

Toward the end of the last session, the patients appeared. Like reluctant guests on some disreputable talk show, they filed in behind a therapist, heads hanging. My mom wore pastel sweats and a full face of makeup. I hugged her thin frame. When she cried, her eyeliner ran.

“I lost 30 pounds,” she said. She didn’t think the loss was related to her enforced sobriety. “All discipline.”

She got permission to take us on a tour. We started in the gift shop, where she tried to buy sweatshirts and tchotchkes, but I demurred, seeing only more dollar signs. From there, we walked to the cafeteria. I poured myself a bowl of cereal. My mom sprinkled undressed lettuce across her plate.

There was only one occupied table. Patients sat together, laughing and eating. I had met some of their family members, and I tried to match faces to stories: the professional swimmer, the prodigal son, the thieving aunt. The program seemed to be working for them.

We passed them without a word. One man — tall, gray-haired — offered my mom a pity nod before looking down at his plate. The rest carried on as if they couldn’t see her. I felt the familiar sting of shame. I had been here before — in seventh grade, at the far end of a lunch table — but it was new for her.

I wanted to cheer her on, like she did for me when she seemed delusionally convinced I should run for student body president, because, well, who wouldn’t vote for you? Instead, I kept my head down and followed her to the loser table.

It was too big for the three of us. My mom moved the lettuce around her plate, continuing her hunger strike. She talked about a sailing trip she was planning for the spring, as soon as she was reunited with her enabling boyfriend. In a low whisper she gossiped about the “druggies” and complained about her counselors. She lied about her benzo usage, broke patient confidentiality, lobbed passive-aggressive barbs. The weight of our failure was crushing.

She led us through a labyrinth of pink-carpeted hallways and underground tunnels, until we arrived at a single that looked like a cross between a dorm room and a hospital room.

“I got these for you,” my mom said. She chucked a bag of Laffy Taffy at my sister.

I looked through the sliding glass door, but it was dark again. All I could see was my own stupid face. All I could see was the money and time we had spent, the things we had said that we could never unsay. All I could see was the ways I was like her.

Mom opened a bedside drawer. She retrieved a bag of carrots stored next to a Bible.

“I want to show you something.”

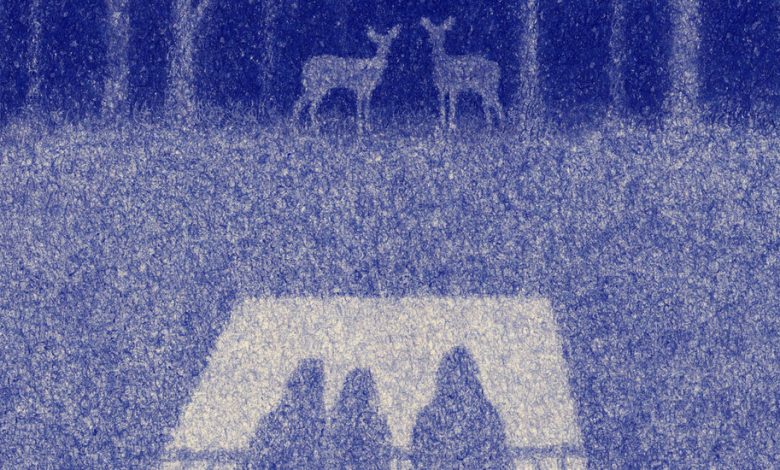

She pulled the sliding glass door open. I followed her onto a balcony into the punishing cold. We were a few feet off the ground, overlooking a meadow. Packed snow covered the ground, pocked with hoof prints.

“Look,” she said, pointing.

Standing at the forest line, like a mirage, were two fawns.

Deer were not exotic. There were so many in New Jersey that they had become a public nuisance. Still, I was mesmerized by the way they approached us — slowly, deliberately.

Emma joined us on the balcony.

Where is their mother? I wondered. The fawns drew close enough that I could see their spots.

“You can feed them by hand,” my mom said. “They’re very trusting.”

She tossed a handful of carrots, and her gentleness bent time, dilated it just wide enough that I could peer into the future. There, she stood beside me under the California sun, cradling one of my babies. Humbled, but upright. Taken apart and rebuilt, plank by plank.

Palm outstretched, she said: “If anything beautiful can come of this, write about it.”

Kate Brody is the author of the novel “Rabbit Hole.” She lives in Los Angeles.