Hickory Dickory Dock. It’s Andrew Dice Clay on TikTok.

The first shot is a crooked view of a sparse Christmas tree on a narrow median in Manhattan traffic. The second is a confused man walking his dog. Then the camera swivels to show us none other than Andrew Dice Clay, tentatively muttering in a “Guys and Dolls” accent, “You wanted a picture in front of the tree with me?”

The man with the dog doesn’t recognize him, his glance shifting from discomfort to pity. “I’ll take a picture of you,” he says condescendingly. Then we return to Clay stammering: “I thought you wanted one? No?”

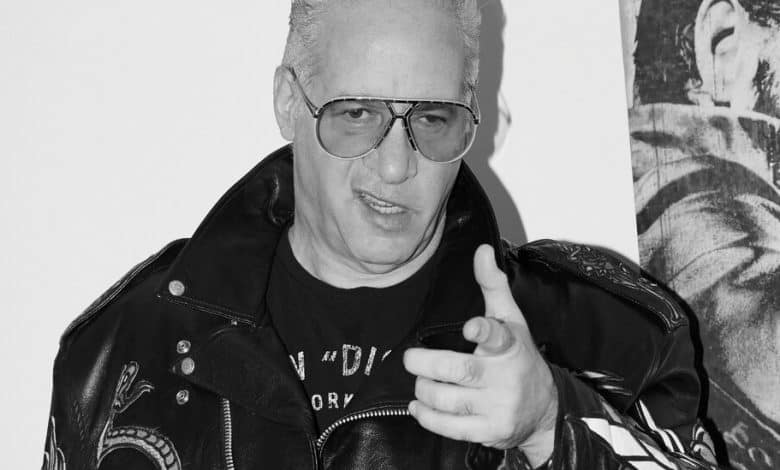

This 14-second-long video is a disarming slice of life, a minor comic humiliation staged with impromptu precision. It’s part of an oddly delightful project undertaken by Clay, the notorious comedian, now in his 60s. He still performs blustery leather-jacketed stand-up (he plays Carnegie Hall on Feb. 15), but he’s portrayed in a very different light in his social media posts: a self-deprecating series of vignettes that clash with his image while also bringing him back to his forgotten roots.

TikTok Dice may come as a surprise to those who remember his swaggering days as the first comic to sell out Madison Square Garden two nights in a row. Whereas he once presented himself as a vain peacock, Clay here comes off as spacey and a bit doddering, swaddled in scarves and wide sunglasses and outfits Susie Essman might wear on “Curb Your Enthusiasm.” People rarely recognize him, but he often acts as if they will, which adds poignancy to the encounters.

Part of the joke of these videos involves fleeting fame. It’s Dice as Norma Desmond, but instead of locked up in a Los Angeles home, he’s prowling the streets of New York, talking to doormen, high school kids, tourists. Most people appear understandably confused, some irritated; one guy with a selfie stick is too focused on himself to pay attention.

Clay was once the poster child for toxic masculinity, boasting his way through jokes that were so sexist and homophobic that this paper likened his shows to Nazi rallies. These videos not only lack any of the rock-star ego of the past; they also show off an entirely new character: rigorously clean, sweetly optimistic, cheerful to a fault, even bizarrely wholesome.

He often presents himself in close-up so his doughy features seem warmly welcoming. He chronicled the lights in New York around Christmas, and his good cheer stands out in a city bustling with fast walkers avoiding eye contact. I was first alerted that Andrew Dice Clay was doing something unusual online by Tom Keaney, David Letterman’s manager, and the interactions do evoke some of the late-night host’s more improvisational remote pieces that used the city as a backdrop.

Clay’s Brooklyn accent was always a bit of a stylized invention, like something out of Looney Tunes, and in these posts he slows it down to sound either babyish or like a grandmother urging you to take seconds. Since his camera tends to focus on others, most of what we learn about this character comes from his subjects, who look concerned or confused.

Some comedy aficionados make the case that Andrew Dice Clay was always as much performance art as stand-up, akin to the character comedy of Pee-wee Herman and Andy Kaufman. When I interviewed Clay years ago, my impression was that if that were so, years of doing the persona had infiltrated his real self so thoroughly that the two had become blurred even in his own mind. But the relationship between an artist on and offstage is often more complicated than it appears.

The argument that his comedy has a self-aware avant-garde streak often leans on his 1990 album, “The Day the Laughter Died,” which he recorded at the intimate New York club Dangerfield’s (now called Rodney’s) around the holidays. It was a stunt, entirely improvised, filled with awkward silence, filthy trash talk and the ramblings of a man who sounds like he’s chattering away to himself.

TikTok Dice has none of the coarse language but does include plenty of the awkward tension and delirious nonsense. In one post, he approaches a man with a mustache outside an airport and asks if he’s the mathematician Vernon Spellcheck. There’s a whole subset of videos where the comic calls people “Big shot” for things like wearing shorts or talking on the phone. “Big shot, no hat,” he tells pedestrians hurrying down what looks like Central Park West.

A Jewish kid from Brooklyn, Andrew Clay Silverstein began his career with an act where he did an impression of a nerdy Jerry Lewis type from “The Nutty Professor” and then transformed into a John Travolta figure. Eventually the cocky Italian guy stuck while the nerd vanished. You could view a scroll through his social media accounts as the reverse story. In early videos, he breaks out Travolta dance moves but finds success playing the nebbish, so sticks with that.

There are echoes of the old Clay, but usually as something to deflate. In one video the week before Thanksgiving, he enters a Whole Foods and launches into a filthy Mother Hubbard nursery rhyme, a performance for one guy. Turning beloved kids’ rhymes into dirty jokes was once his signature bit, earning roars from arenas. Right before the punchline, the audience of one gets distracted, and Clay stops. The stranger apologizes and says, “I wasn’t listening.”

On one album, Clay refused an audience request to do the nursery rhymes. Now he volunteers it to people who don’t care and he posts the results. His comedy has been so polarizing that it’s easy to miss what a gifted performer he is — the timing of his delivery, the undeniable presence. Even if you hate him, it’s hard to deny that the guy is fun to imitate — you hear his influence in the snap of the voices of Natasha Lyonne (who gave him a shout-out on her series “Russian Doll”) and the comic Robby Hoffman. There was nothing exactly like Clay before him. And there’s nothing exactly like his current hypnotic feed. I find myself captivated by how easily he abases himself without getting maudlin.

There’s one video in which a fan gets excited to see him, but Clay acts so stammeringly that the fan loses faith that it’s the right guy. In another, Clay whispers to a young hipster in a bank, “I can see you’re a giant fan and want a picture,” to the most befuddled of looks.

Andrew Dice Clay never gets angry or especially upset in these videos. And his optimism that people will want a photo with him doesn’t flag. He keeps announcing that he’s “the international face of fame.”

One of the few times another celebrity appears takes place toward the end of a video of him approaching people at an airport. He goes up to a guy at a bar who turns out to be Matt Damon. The actor seems to draw a blank, but the camera cuts away before we find out more. In this scroll, celebrities don’t get preferential treatment over anyone else. Fame and controversy come and go, but being singular lasts.