Sir Ben Ainslie is smarting from a public sporting divorce from Sir Jim Ratcliffe, the British billionaire and part-owner of Manchester United.

“It’s probably the most difficult thing I’ve ever been through in my life, from a personal or a sporting perspective,” Ainslie, a four-time Olympic champion and majority owner of Britain’s SailGP team, tells The Athletic of the end of his America’s Cup partnership with the INEOS founder and chairman.

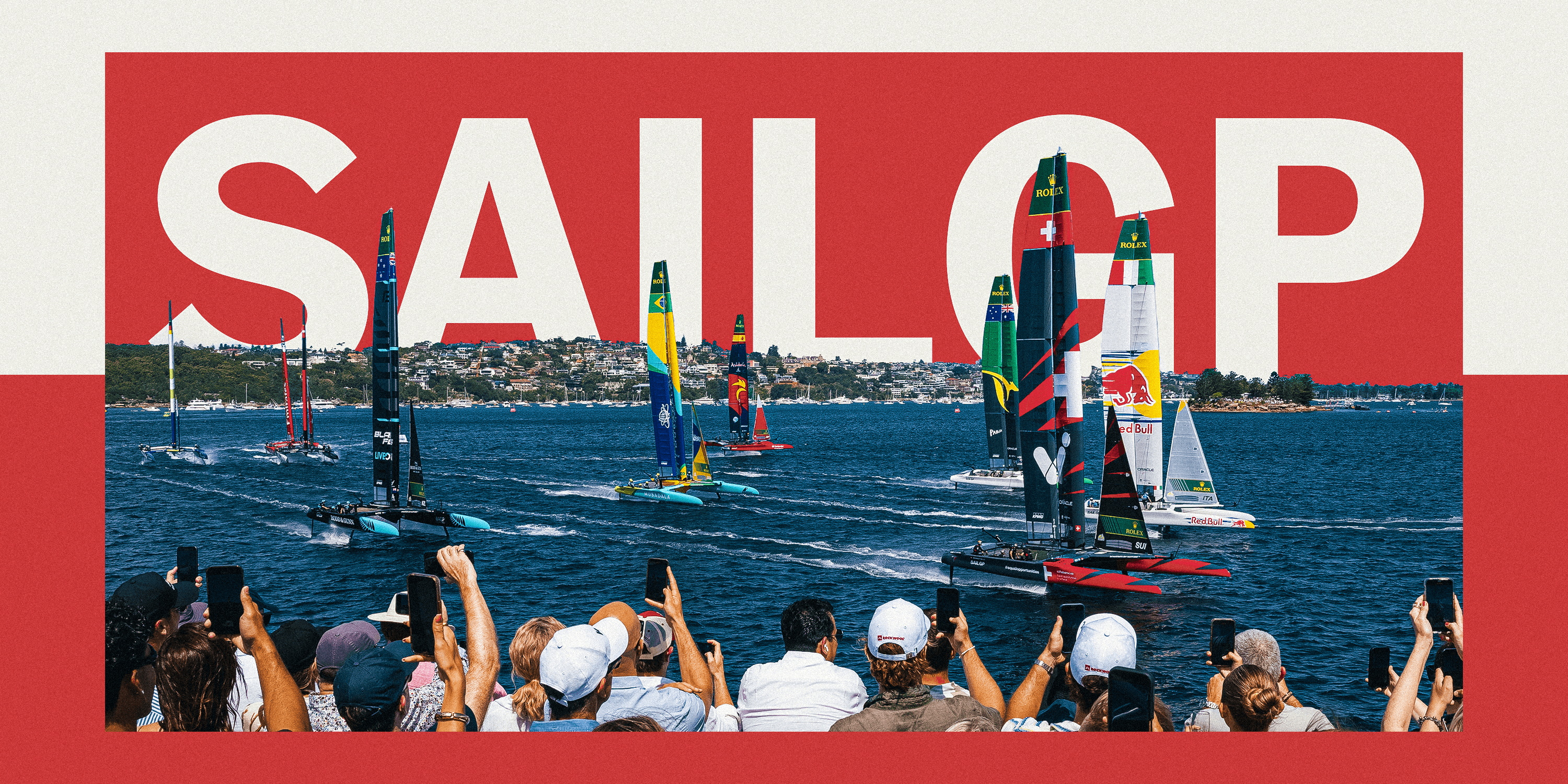

The 48-year-old first spoke to The Athletic a little over a month ago at the SailGP event in Los Angeles, when Ratcliffe was still going forward with his separate British challenge for the America’s Cup, a 174-year-old international competition traditionally regarded as the pinnacle of the sport. The initial interview was mainly a conversation about SailGP, with Ainslie’s team flying high and lying second overall in the championship.

But since that initial conversation on the Californian coast, there have been several developments in the America’s Cup, not least Ratcliffe’s shock withdrawal from the event. So, Ainslie was keen to bring us up to date with his latest thoughts. That said, he was more eager to talk about where things were going with the next America’s Cup, much less enthusiastic to rake over the coals of that split with Ratcliffe, one of the UK’s richest men who made his fortune with the petrochemicals company INEOS.

“We’re dealing with it, but we have the core of the team, we’re still on that journey,” says Ainslie, frustrated but also relieved to be master of his destiny once more.

The Briton’s ambition to win the America’s Cup remains undiminished. After all, it’s the oldest trophy in international sport, involving the reigning champion taking on a challenger in a match race, and one Britain has never won.

“We set out to win the cup and we’re determined that we’re going to keep going until we get that job done,” he adds.

That two of the most recognizable names in UK sport, both Knights of the Realm, both hugely successful in their respective fields, have gone their separate sporting ways has unsurprisingly been of interest to those outside the world of sailing. The most recent chapter came earlier this month when INEOS Britannia announced its withdrawal.

INEOS alleged its decision was due to the “protracted negotiations” with Athena Racing, which Ainslie founded.

Asked if he had a response to INEOS’ most recent statement, Ainslie — the skipper and CEO of Great Britain’s America’s Cup challenge for the past decade — was reticent. “I don’t know, I don’t really want to get drawn on that,” he says. “I think most people can probably see it for what it is. We’re just focused on our own role, as Challenger of Record, and continuing to pull forward, trying to win the cup for Britain.”

Nearly three months ago, it was announced that Ainslie, INEOS Britannia’s former team principal and skipper, had left the team. At the time, INEOS said it still intended to compete at the 38th America’s Cup under the Britannia name, a plan Athena said it was “astounded” by.

Fast forward to the beginning of April, and INEOS said an agreement had been reached to allow both INEOS and Athena to compete in the next America’s Cup, but said in its statement that Athena’s failure to “bring the agreement to a timely conclusion” had impacted INEOS’ preparations and led to its withdrawal.

Since Ratcliffe completed a 25 percent acquisition of Manchester United in February 2024, a stake since slightly increased, interest in the billionaire has rocketed, from his running of England’s most successful soccer team to the other sports in his wide-ranging portfolio, such as cycling and, until recently, sailing.

But Ainslie’s involvement with the Manchester-born Ratcliffe is no more. His ambitions, however, remain lofty.

He still wants to compete in the America’s Cup, but having been dropped by his former backer, Ainslie needs to find large amounts of money — and quickly — if he has any serious prospect of continuing his quest to win the prestigious event which has a heavy reliance on private patronage.

Ainslie retains the assets from the last campaign, not least Britannia, the AC75 boat that got quicker and quicker throughout the 37th edition of the cup last year in Barcelona. Most of his team is still in place, but Ainslie needs funds and for that he needs clarity from the holders, Team New Zealand, specifically over where the event will be held.

In his role as Challenger of Record, Ainslie is negotiating with Grant Dalton, CEO of Team New Zealand, to shape the terms of the 38th America’s Cup, specifically where and when it will be held. Though yet to be confirmed, it seems that Dalton, who will also set the rules for the next edition, is aiming for 2027.

Being Challenger of Record doesn’t guarantee Ainslie’s Athena Racing a place in the title-deciding match. His team will have to overcome a number of other challengers in a series of regattas to earn the right to take on New Zealand in the first-to-seven-points final itself. It’s a long road to win a competition heavily skewed in favor of the defending team.

But after battling his way to four successive Olympic gold medals, winning the America’s Cup has been Ainslie’s obsession for more than 20 years. While he was a key part of the crew that won the 2013 edition in San Francisco for U.S. tech billionaire Larry Ellison, Ainslie wants to win it on his terms, for his country. Ever since that taste of victory 12 years ago, Ainslie has been on a determined quest to bring the Auld Mug back to Britain.

Yet, even such a passionate enthusiast of the America’s Cup like Ainslie can see how the world is changing, and changing fast, which brings us to his involvement in SailGP as owner of the British team in the international grand prix sailing competition now in its fifth season.

The championship is on a roll, and making the slow-moving developments in the America’s Cup look more glacial than ever. Like many before him who have tried and failed, Ainslie desperately wants to drag the America’s Cup away from its traditional, Corinthian roots and move the event to a more modern, commercially viable footing.

“I think SailGP is doing a brilliant job for the sport and showcasing what is possible,” says Ainslie, who was the first to buy a national SailGP team franchise three years ago.

When he co-founded SailGP with Ellison, Russell Coutts aimed to cut sailing free from the apron strings of private patronage and transform the sport by introducing an annual close-to-shore championship which would attract the mainstream. Having expanded from an initial six-team league to 12 (and plans have been confirmed to expand to 14 teams in 2026), the SailGP championship has been designed to grab attention, from the identical boats each country competes in head-to-head to the sudden-death format which determines the winner of a Grand Prix weekend and, ultimately, the championship. SailGP is the antithesis of the America’s Cup, a competition encumbered by tradition and complications.

“When you’ve got coordination around the scheduling, then your venue partners, your commercial partners, your broadcast partners all start to fall into place,” adds Ainslie of SailGP. “It’s clear that the sport has been missing that, and SailGP has filled that void, which is absolutely fantastic. What it shows is that the America’s Cup has huge potential because of the history and the prestige of the event.

“What we need to do for the sport of sailing is find a way for SailGP and the America’s Cup to complement one another. America’s Cup should not be trying to create a competing league to SailGP. That would just be absolutely, mind-boggingly stupid because SailGP has done that. It has invested a huge amount of money getting to where it is now. And it’s still growing. It’s got a great, great trajectory ahead of it.”

For commercial and emotional reasons, Ainslie needs to see both events thriving alongside each other.

But in the latest sign of just how SailGP is increasingly threatening the America’s Cup’s long-held status as the undisputed pinnacle of professional sailing, New Zealand will be defending their America’s Cup title without its most feted professional sailor, who has decided to step away from a fourth campaign.

After protracted negotiations with Dalton, Peter Burling chose SailGP, focusing his time on the Black Foils and his young family.

It’s not often a professional sailor walks away from perhaps the most prestigious job in sailing. At just 34 years of age, Burling is not over the hill. Most America’s Cup skippers have barely embarked on their first campaign at his age, let alone won three. Considering the America’s Cup is 174 years old and SailGP just six, it’s a surprising decision for Burling to have taken.

Asked in an interview with New Zealand radio station Newstalk ZB about whether it was possible for the top professionals to be active across both events, the Team New Zealand boss said his sailors had to race. “It’s a league and they’re completely complementary in so much as we’re the World Cup and they’re the Champions League, if you like,” he said. “So it’s only good for the sport. But if there comes a time when they clash — and I think they will clash in 2027 — then it’s naive of anybody to think that you can do both.”

Ainslie called for “careful scheduling” as he wanted to see sailors of Burling’s caliber on the start line for the 38th America’s Cup. Anything different would, in his view, diminish the stature of the event.

“I think any clash of events is a mistake because it’s taking oxygen away from one another, and it should be supporting one another. Plus, both events require and deserve the very best sailors in the world,” the Englishman says.

Ainslie also pushed back on the notion that SailGP played second fiddle to the America’s Cup. “One thing I would say is SailGP is not a training ground for the America’s Cup,” he says. “It’s there in its own right as a league. I think if you speak to any of the top sailors in the world — and certainly it’s my view — you’re racing in SailGP for keeps. It means a lot to be one of the top teams, or to win the SailGP league.

“Absolutely, what the America’s Cup should not be doing is trying to take on SailGP head-on because I think that ship has sailed. Full credit to Russell and the team at SailGP, they’ve done a phenomenal job building the league out to what it is now, and still growing,” he adds.

“That’s not where the America’s Cup should try to place itself. It should draw on its roots of the huge history and prestige of the event and focus on this special event status, which is almost unique to the America’s Cup.

“There aren’t many other sporting events out there which hold that level of prestige and history.”

(Top photo: Lluis Gene/AFP via Getty Images)