The Death of Iran’s President Does Not Bode Well

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has not always seen eye to eye with his country’s presidents. Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani nudged the Islamic Republic too close to the West for the supreme leader’s liking. Mohammad Khatami rattled the conservative elite with subversive talk of how faith and freedom could coexist. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was too insubordinate and too populist, while Hassan Rouhani’s flirtation with the Americans and his disappointing arms-control agreement drove him out of the inner circle.

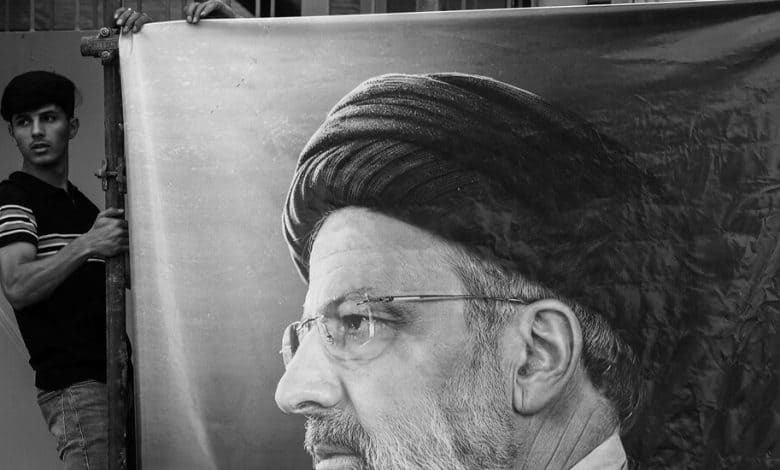

President Ebrahim Raisi, on the other hand, was Mr. Khamenei’s ideal partner. A lackluster manager with dispiriting rhetoric and a vicious streak, he was steadfastly loyal to Mr. Khamenei, who is 85 years old, and an integral part of his plan to ensure a smooth succession. Mr. Raisi’s sudden death in a helicopter crash on Sunday has thrown that plan into disarray, scrambled Iran’s backroom politics and could further empower a younger, more radical generation of politicians that would bring further repression at home and aggression overseas.

Mr. Raisi was a revolutionary with an ideologue’s integrity. Early on he was appointed to various prosecutorial roles, where he regularly sought — and secured — the execution of regime opponents. In 1988, he firmed up that reputation by serving on the so-called death commissions that executed upward of 5,000 political prisoners. He then spent much of his career in the regime’s darker corners, becoming the head of the judiciary before being elevated to the presidency.

Despite this deep experience and loyalty, it wasn’t clear that Mr. Raisi would be a suitable successor to Mr. Khamenei, a development many observers and Iranians feared. The challenge of managing a government at odds with much of its population and the international community requires an unusual mixture of cunning, intelligence and cruelty. Mr. Raisi only possessed the last. But even if his ascension was uncertain, Mr. Khamenei still relied upon the cleric to help manage the coming transition: Mr. Raisi was reportedly part of a three-man committee vested with the responsibility to choose the next supreme leader.

Mr. Khamenei will now need to find someone else as reliable to execute, as ruthlessly as required, his vision, and arrange another contrived election to install him. This will not be easy: Iran’s political system has been so relentlessly purged of those present at the creation of the republic that little of the old establishment is left.

The new political landscape is largely dominated by younger men who openly lament the older generation’s corruption, lack of revolutionary zeal and unwillingness to take on more forcefully a fading American imperium. And because Mr. Khamenei must rely on this new group to sustain the revolution’s values and keep the theocracy intact, he will have to take their sensibilities into account as he considers both the next president and who should succeed him as supreme leader.