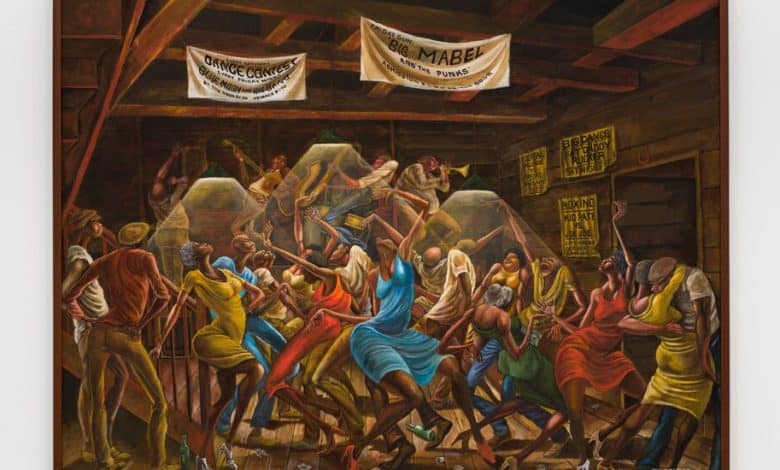

Ernie Barnes Paints What It Feels Like to Move

The second thing you notice about an Ernie Barnes painting might be its vibrant color scheme. Anchored in earthy reds and browns, it perfectly complements the artist’s virtuosic, almost musical mastery of space and composition. Or it could be the overflowing warmth with which he depicts Black American life that catches your eye. If the painting is “The Sugar Shack,” you might recognize it from an appearance on the 1970s sitcom “Good Times,” where it was shown during the closing credits;fromthe cover of Marvin Gaye’s 1976 album “I Want You”; or from its dramatic sale for more than $15 million in 2022. You may also have encountered one of the thousands of posters and prints which, throughout his career, he made available at modest prices.

The first thing you notice about an Ernie Barnes painting will be the distinctively sinuous way he renders human beings.

Barnes, who died in 2009 at age 70, called his style “Neo-Mannerist” after the 16th-century Italians, and you can draw connections to 20th-century artists, too. (I personally think of Chagall.) What I hadn’t realized till seeing “Ernie Barnes: In Rapture,” an expansive and generous five-decade survey presented at Ortuzar Projects in Manhattan, in collaboration with Andrew Kreps Gallery, was just how precisely Barnes’s unique lines capture the anatomical and experiential details of bodies in motion.

In “Dead Heat,” Barnes, an athlete himself who played professional football before getting a job painting the New York Jets, models every quad muscle on each of three straining sprinters separately, as if for a medical diagram. The same kind of exaggerated specificity reveals the grace behind gestures and expressions which, in real life, would pass too quickly to catch: the toes pointed like a dancer’s, the neck craning toward the finish, the chest that arcs itself forward to break a billowing, ornamental line of bright blue tape.