In Immunity Decision, Clashing Views of the Nature of Politics

Near the end of his opinion on executive immunity, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. pooh-poohed the fears of his liberal colleagues who worried in dissent that the broad protections the Supreme Court had conferred on former President Donald J. Trump would place future presidents beyond the reach of the law.

The real concern, Chief Justice Roberts said, was not that immunity would embolden presidents to commit crimes with impunity, but rather that without it, the country’s rival leaders would endlessly be at each others’ throats.

“The dissents overlook the more likely prospect of an executive branch that cannibalizes itself,” he wrote, “with each successive president free to prosecute his predecessors.”

That dark vision, however right or wrong it proves to be, did not come out of nowhere: It was offered to the court by Mr. Trump’s own lawyers during oral arguments on the question of immunity that took place in April.

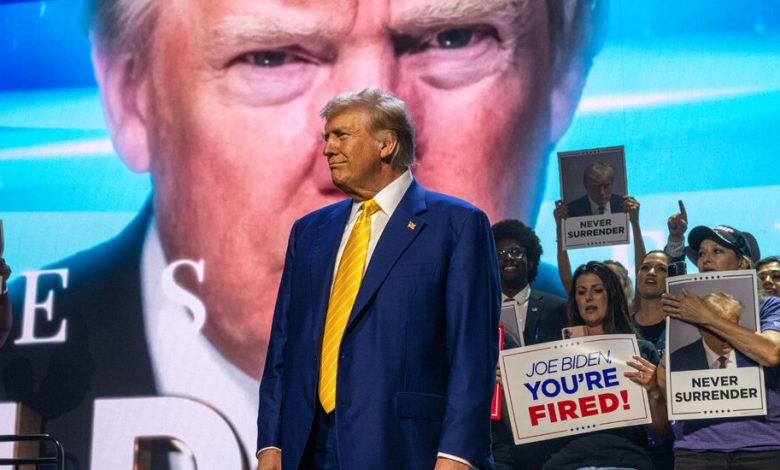

The justices in the majority said their decision was not just about Mr. Trump. But it was impossible to separate it from the possibility of a second Trump presidency following a campaign in which Mr. Trump himself has promised unabashedly to use the legal system as a weapon of political retribution against President Biden and other foes, whom he accuses of having unfairly targeted him for prosecution.

In many ways, the court’s decision was something like a Rorschach test for the justices, revealing what they saw as the largest looming threat to American democracy.