My Friend Won’t Leave Her Abusive Husband. What Do I Do?

I have a good friend whom I love and care about. She is married to a man whose alcoholism has gotten worse over the years; he is also both verbally abusive and controlling of her. They have a son who is 12. My friend participates in Al-Anon, a support group for friends and family of alcoholics, and is also going to therapy. We talk about once a week, and she tells me awful stories about her husband’s drinking and subsequent abuse. I have talked to her about leaving, and emphasized the support that I and other friends would give; she maintains that she is not ready to leave. (She has a good job with benefits and salary, so it’s not a financial issue.)

I’m never sure what I can say to let her know that I support her but think her husband’s abuse of her is unacceptable. I heard a podcast on this subject advising saying something like, “I know how smart you are and that you’ll know when to leave,” and I’ve used that line a lot.

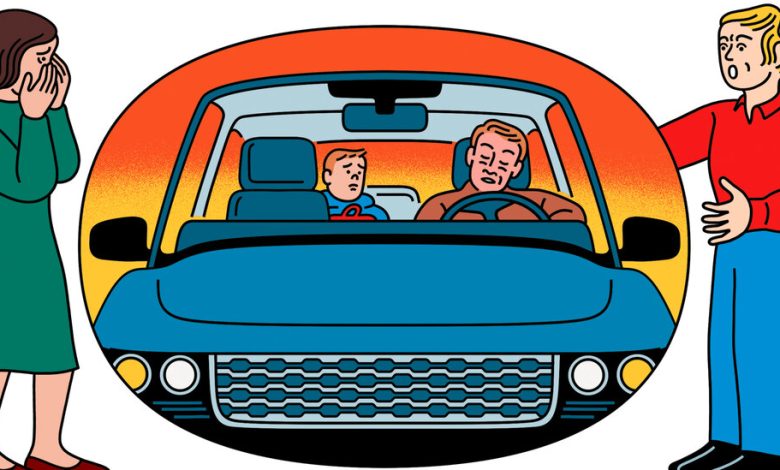

Recently, her husband picked up her son from a friend’s house and drove with him while drunk. This still did not cause her to take her son and leave. I really don’t know what to say anymore. Name Withheld

A proverb from my part of Ghana says, “Marriage is like a groundnut; you must crack it to see what is inside.” It’s hard to figure out what’s going on in other people’s relationships. In particular, there’s no one-size-fits-all answer to why people stay with abusive partners long after their friends have all concluded that they should leave. Although your friend offers you no explanation for why she remains with her abuser, the fact that she regularly tells you about his appalling behavior indicates that she is highly aware of the problem and seeks corroboration and support from you.

So far as I can tell, you’ve done all the right things: You’ve made it clear to her that she is a person of value, that she doesn’t deserve to be treated this way, that she isn’t alone and that she’ll have a good network of support if she chooses to leave. You’ve let her know too that you understand the suffering her husband is causing and the menace he poses, helping her see her situation as clearly as possible.

It’s certainly a dismaying one. While alcoholism can worsen domestic abuse, it doesn’t entirely explain the propensity to engage in abuse. And given that he’s driving their son around when he’s drunk, he’s a danger to both of them. But, as you recognize, the decision to leave is ultimately hers to make. Even if the abuse rises to the level of a crime, the police are unlikely to be able to do anything about it unless she confirms what’s happening.

She’s fortunate that she has someone like you with whom she can discuss her husband’s conduct. You’ve preserved the relationship because you’ve found a way to dissent from her misguided loyalty to her husband without tearing her down. Keep asking her what you can do to help. And though you can’t dictate what she can do, promptings can be made in the spirit of friendship.

Like you, I worry about the danger to her son. According to a 2014 analysis of C.D.C. data, nearly two-thirds of children who die in impaired-driving crashes are passengers of the impaired driver. Driving drunk is, to be blunt, a typical way that parents kill their children.

Ideally, your friend would take pains to ensure that her son was never in a position to be driven by her husband. At the very least, you could suggest that she instruct the boy not to get into the car if his father shows up drunk. (For that matter, the friend’s parents shouldn’t have let him be driven by a man showing signs of intoxication.) She could give him access to a ride-share account and tell him to use it instead. It would probably be best if she told her husband that she was doing this. But she may be too afraid of her husband to take such measures, and she would have to make a judgment about whether that would make her son a target of abuse.

Whatever your friend does, she ought to discuss the situation with her son, who must already be aware of some of what’s going on. Therapy could be helpful to him, too. Discussing these options with her will reinforce the reality that her husband is a threat to her son as well as to her — and further motivate her to move them both out of harm’s way. Being a bystander to this sort of horror show can make a person feel powerless. You’ve made it plain that you’ll walk with her to the exit. All you can do is stay with her and hope she’ll take the necessary steps.

I’ve been divorced for more than 40 years. Long after the divorce, my ex went to prison for having sex with a teenage girl. He was also physically abusive to me. Currently he is a conspiracy theorist and an anti-vax zealot. He has been out of touch with our now 40-something son for more than three decades.

Recently he found me and is asking for our son’s contact info. I’m terrified of my ex. He’s a Vietnam vet with a head injury. Although he’s in his 70s, he is truly a violent, terrifying person. I’m in therapy dealing with PTSD from my time with him. Still, this is my son’s biological father.

A further complication: My son and I have been estranged for five years, since my mother died. I am no prize. I failed my son as a mother in every respect, so I feel ill equipped to judge. (I don’t make or accept excuses for mental illness.)

What is my responsibility here? Am I wrong not to share my ex’s contact information with my son so he can decide for himself? I’ve struggled with this for over a year. Because my ex is in his 70s, if I don’t do anything, this decision may soon be out of my hands. Name Withheld

It’s heartbreaking to contemplate a sequence of events in which a man who may be suffering from PTSD himself behaves in such a way as to induce PTSD in others. But it’s not for you to decide whether this septuagenarian and this middle-aged man should be in touch; the choice is your son’s. Your relationship toward your son is clearly fraught with guilt and self-reproach. You care deeply about your son’s safety. Yet I fear that your desire to protect him has led you to disrespect him.

Ask your son, perhaps in a written message, what he would prefer. You can stress your concerns, so that you feel assured that his decision is fully informed. And if your son does want to establish this connection, you can suggest, say, that he propose to meet first in a public place, allowing him to break off contact more easily if that seems best. What you shouldn’t do is to take the choice out of his hands.

Recently, a friend at work, who is an excellent physician and very caring toward his patients, made a horrifying comment about the Holocaust. I was literally shocked into silence. Some of the other doctors at the table let out embarrassed laughs. I believe that this person is aware that my wife is Jewish. I feel terrible that I didn’t say anything. Can I bring up the issue with him now, weeks later? It also might mean the end of our friendship. What to do? Name Withheld

If a friend says something that, weeks later, still weighs on your mind, you really should let the person know. Maybe this man will offer a genuine apology, or persuade you that, while his words were poorly chosen, he hadn’t meant to say what you took him to be saying. In those circumstances, speaking up might save a friendship that, I suspect, will wither if you don’t reveal what’s on your mind. Having that difficult conversation could provide an opportunity to address and perhaps resolve the sense of outrage you feel.

Then again, maybe your colleague will remain unmoved and unrepentant, leaving you with a decision to make. Yes, friends can have differences of opinion on a range of topics. But someone who reveals a moral void within himself may be undeserving of friendship.

Kwame Anthony Appiah teaches philosophy at N.Y.U. His books include “Cosmopolitanism,” “The Honor Code” and “The Lies That Bind: Rethinking Identity.” To submit a query: Send an email to [email protected]. Want The Ethicist directly in your inbox? Subscribe to our new newsletter.