What Should We Expect of Art?

What is art supposed to do? One could argue that the question itself is something of a trick, as it assumes that art is meant to do anything other than just exist. And yet throughout history, art has been expected to fulfill some greater duty or responsibility: religious instruction, the glorification of a ruler, moral uplift and education.

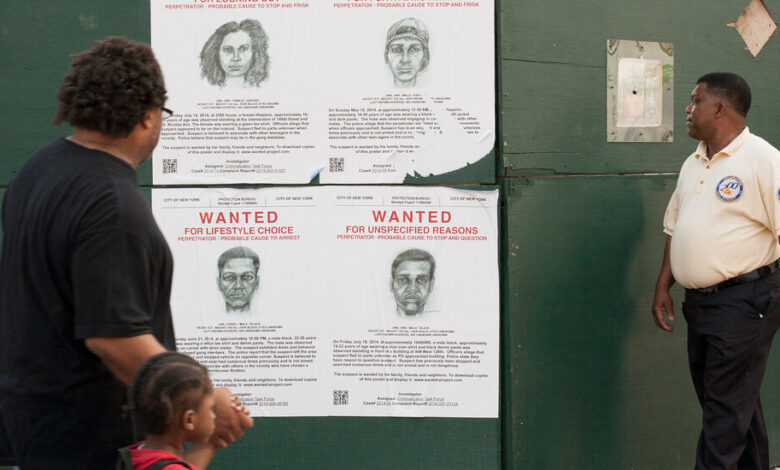

We are currently in a moment in which art is often expected to say something about the various urgent injustices that define our world — and not just to say something but to be a conduit for change. This has led to some provocative and moving work, proof that sometimes art can do what policy alone cannot: shift public perception and provide an emotional entryway into a problem that can feel either abstract or intimidatingly complex (or both). In his story for T, writer at large Adam Bradley visits with the artists making work about (and sometimes within) the American carceral system. As Bradley writes, “more than 113 million Americans have an immediate family member who has been to prison or jail”; Black Americans, who comprise less than 15 percent of the U.S. population, represent 38 percent of the country’s incarcerated population. For many of the artists engaging with the topic, the line between creation and activism is necessarily thin; art is a calling, but it’s also a mission.

But there’s no one way to be an artist. As Amanda Fortini writes about the 95-year-old painter Alex Katz, “his concerns are essentially technical and formalist … rather than narrative or expressionist. … His paintings neglect to propound a narrative, a concept or a political message, embodying an approach that’s also not very popular right now.” What Katz has done instead, she argues, is develop a singular and inimitable aesthetic, one that blurs the boundaries between figuration and abstraction, and has over his multidecade career consistently challenged what a painting should be. This, too, is art, and this, too, is a mission. “This is the highest thing an artist can do,” Katz once said, “to make something that’s real for his time, where he lives.”

On the Covers

And then there’s us, the audience. What is our role in the artist’s life? It’s to look, of course, and to do so closely, and with generosity. And sometimes it’s to champion — to be, in a sense, activists ourselves. In his essay, editor at large Nick Haramis talks to a group of collectors who are buying works by gay artists who were active in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s, many of whom died from complications from AIDS when they were in their 30s and 40s. AIDS deprived them of a long artistic life, but not a full one, and these collectors are making sure their names and legacies aren’t forgotten — and that they’re given their deserved places within museums and galleries, not to mention the annals of contemporary art. But these collectors are doing more than just forcing a reconsideration of this art; “by living with [these works], they keep the memory of the AIDS era and its people alive,” Haramis notes. They are a reminder of the relationship that has always existed between the artist and the rest of us. Art may not be obligated to change our lives, but it often does anyway — we are one person when we come to a piece; we are another when we walk away. And what greater mission is there than that?