Do We Still Understand How Wars Are Won?

In the past 50 years, the United States has gotten good at losing wars.

We withdrew in humiliation from Saigon in 1975, Beirut in 1984, Mogadishu in 1993 and Kabul in 2021. We withdrew, after the tenuous victory of the surge, from Baghdad in 2011, only to return three years later after ISIS swept through northern Iraq and we had to stop it (which, with the help of Iraqis and Kurds, we did). We won limited victories against Saddam Hussein in 1991 and Muammar el-Qaddafi in 2011, only to fumble the endgames.

What’s left? Grenada, Panama, Kosovo: micro-wars that incurred minimal U.S. casualties and are barely remembered today.

If you’re on the left, you’d probably say that most if not all these wars were unnecessary, unwinnable or unworthy. If you’re on the right, you might say they were badly fought — with inadequate force, too many restrictions on the way force could be used or an overeagerness to withdraw before we had finished the job. Either way, none of these wars were about our very existence. Life in America would not have materially changed if, say, Kosovo were still a part of Serbia.

But what about wars that are existential?

We know how America fought such wars. During the siege of Vicksburg in 1863, hunger “yielded to starvation as dogs, cats, and even rats vanished from the city,” Ron Chernow noted in his biography of Ulysses Grant. The Union did not send food convoys to relieve the suffering of innocent Southerners.

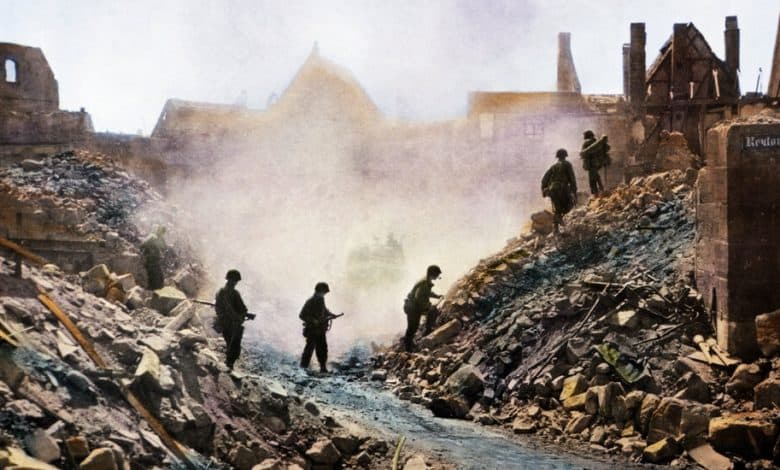

In World War II, Allied bombers killed an estimated 10,000 civilians in the Netherlands, 60,000 in France, 60,000 in Italy and hundreds of thousands of Germans. All this was part of a declared Anglo-American policy to undermine “the morale of the German people to the point where their capacity for armed resistance is fatally weakened.” We pursued an identical policy against Japan, where bombardment killed, according to some estimates, nearly one million civilians.

Grant is on the $50 bill. Franklin Roosevelt’s portrait hangs in the Oval Office. The bravery of the American bomber crews is celebrated in shows like Apple TV+’s “Masters of the Air.” Nations, especially democracies, often have second thoughts about the means they use to win existential wars. But they also tend to canonize leaders who, faced with the awful choice of evils that every war presents, nonetheless chose morally compromised victories over morally pure defeats.