Trump’s Tastes in Intelligence: Power and Leverage

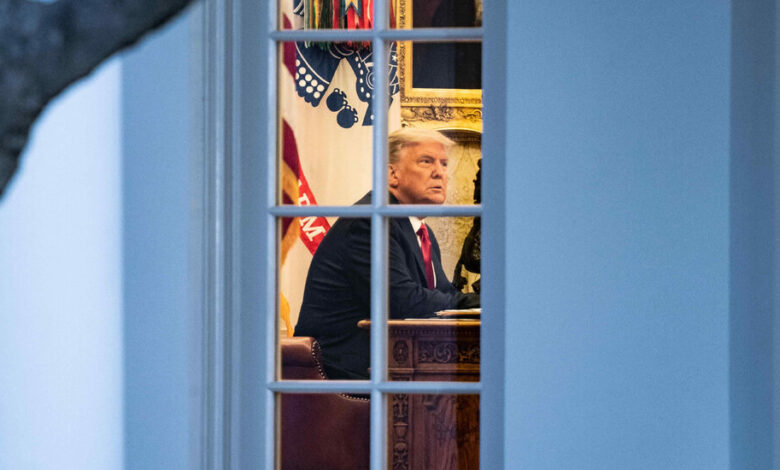

WASHINGTON — As president, Donald J. Trump showed the most interest in intelligence briefings when the topics revolved around his personal relationships with world leaders and the power available at his fingertips.

He took little interest in secret weapons programs, but he often asked questions about the look of Navy ships and sometimes quizzed briefers on the size and power of America’s nuclear arsenal.

He was fascinated by operations to take out high-value targets, like those that led to the deaths of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of the Islamic State, and Maj. Gen. Qassim Suleimani, a top Iranian commander. But the details of broader national security policies bored him.

Unlike some of his predecessors, Mr. Trump did not care about intelligence reports about U.F.O.s, but he would ask questions about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Mr. Trump’s appetite for sensitive information is now at the heart of the criminal investigation into his handling of hundreds of classified documents he kept at his Florida home after leaving office.

The subjects covered in the material he kept remain unknown, and the questions of why he took it in the first place and why he resisted returning it remain unanswered. The intelligence agencies have yet to fully assess the risks to national security, though they plan to do so at the urging of lawmakers in Congress, including the top Democrat and Republican on the Senate Intelligence Committee.

But a look at what most engaged Mr. Trump during intelligence briefings, based on interviews with former Trump administration officials and people involved in providing intelligence reports to him, suggests that he was often drawn to topics that had clear narratives, personal elements or visual components.

The officials offered differing perspectives on how often Mr. Trump kept documents and how many he kept. Some said that materials were gathered back when briefings were over, while others said Mr. Trump somewhat regularly asked to hang onto things, particularly images or graphics.

“Intelligence briefers tried to find a way to get inside his head and would bring along a picture — a chart or a graph or something like that — and hand it to him across the Resolute Desk,” said John R. Bolton, a former national security adviser to Mr. Trump. “Sometimes he would say: ‘Hey, this is interesting. Can I keep this?’”

But there is broad agreement about what sorts of classified information interested Mr. Trump and what bored him. Mr. Bolton recalled once trying to brief him on arms control during a World Cup soccer game and struggling to get his attention.

More on the Trump Documents Inquiry

- Special Master: Former President Donald J. Trump is seeking an independent review of documents seized from his residence in Florida — a move that could lead to appeals and delay the inquiry.

- Unintended Consequences: With his request for a special master, Mr. Trump inadvertently offered the Justice Department the chance to strike back with a revealing court filing laying out evidence of possible obstruction of justice.

- A Revealing Filing: The filing painted the clearest picture to date of the Justice Department’s efforts to retrieve documents from Mr. Trump’s home in Florida, suggesting that classified materials stored at the residence were likely moved and hidden as the government sought their return.

- Under Scrutiny: Two lawyers for Mr. Trump are likely to become witnesses or targets in the investigation after new details emerged about their handling of a subpoena seeking additional material marked as classified.

By the end of the administration, Mr. Trump had come to see the intelligence community’s insights into world leaders as valuable, according to former officials.

Mr. Trump devoured intelligence briefings about his foreign counterparts before and after calls with them. He was eager to deepen his relationships with autocrats like Kim Jong-un of North Korea or Xi Jinping of China and to get leverage over allies he took a personal dislike to, such as Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany, President Emmanuel Macron of France and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau of Canada. Among the materials that the government retrieved from Mar-a-Lago was a document listed as containing information about Mr. Macron.

He was also fascinated by information in his intelligence briefings about how his meetings with world leaders had been received.

“He is all about leverage,” said Sue Gordon, a former principal deputy director of national intelligence. “It is not my experience that he has an ideologically held view about anything. It’s all about what he can use as leverage in this moment.”

With many world leaders, Mr. Trump, whose own dalliances were the stuff of gossip columns for years, was fascinated by what the C.I.A. had learned about his international counterparts’ supposed extramarital affairs — not because he was going to confront them with the information, former officials said, but rather because he found it titillating.

For people briefing Mr. Trump, some of whom were familiar with his penchant for blurting out secret information and had grown hesitant to relay everything to him, his interest in hanging onto documents sometimes created anxiety.

But ultimately, they recounted, saying “no” to the president of the United States in such settings was not seen as an option.

Mr. Trump had a formal intelligence briefing twice a week for much of his time in office. But there were myriad other ways he was given classified information: prep sessions before meetings or calls with world leaders, discussions in the Situation Room, briefings on strikes by Pentagon leaders and informal visits to the Oval Office by the national security adviser. Sometimes Mr. Trump would request that the National Security Council staff bring him classified documents.

Mr. Trump did not always like going to the Situation Room or even the Oval Office for some special briefings. Pentagon officials briefed him on the plans for the Special Operations raid to kill Mr. al-Baghdadi from the Yellow Oval Room, part of the White House residence with a sweeping view of the Washington Monument. At that briefing, senior officials handed numbered visual aids to the president and collected them after.

Still, several former officials interviewed for this article who remembered Mr. Trump occasionally taking a document from a classified briefing or requesting a document from the National Security Council staff said the material he collected in those instances could not have added up to the hundreds of pages in dozens of boxes retrieved by the government from Mar-a-Lago.

Many people interviewed for the article declined to be named, citing either concerns about conveying specific information given to a president in a sensitive setting, the ongoing Justice Department investigation or Mr. Trump’s mercurial temper.

Mr. Trump almost always took great interest in military and intelligence briefings about Iran, quizzing defense officials about their contingency plans for a war with the country and asking detailed questions about secret operations to counter Tehran in the Middle East. But his enthusiasm sometimes left intelligence officials rattled, such as when he posted to Twitter a photo of an Iranian missile launch site taken from an intelligence briefing.

In a matter of days, academics and outside experts used the image to determine which spy satellite took the picture and refine their assessments of the capabilities of its camera.

The control of classified information varied greatly at different points in the administration. And not every official could successfully retrieve a document that Mr. Trump took an interest in, former officials said.

“For Trump, every time you ask for something back, it implies you don’t trust him,” Mr. Bolton said, adding that the briefers would not always succeed when they did ask.

Mr. Trump used, but did not trust, burn bags, the accepted system to destroy classified documents that is employed at the Pentagon, the C.I.A. and elsewhere. Mr. Trump did not believe that the material would actually be burned, former officials said. Officials working closely with Mr. Trump came to learn that in certain cases, when he wanted something destroyed — often paper with his handwritten notes — he would tear it up and toss it in a toilet.

When Mr. Trump decided to keep some material, he would sometimes place it in a cardboard box near his desk. The box was originally meant for unanswered letters, unread briefing books and unread newspapers. While Mr. Trump often read the newspapers and magazines, he rarely, if ever, got to the briefing books, a former senior official said.

When one box was filled, it would be taken away and a new box would appear. Staff members would take the boxes with Mr. Trump when he traveled, allowing him to complete correspondence or catch up on news stories while on Air Force One.

Former officials interviewed for this article said they did not recall ever witnessing classified material going into the box. But several emphasized the chaos that gripped the White House in the final days of the administration, as staff members had to pack in secret to avoid being ordered to stop by Mr. Trump, who continued to assert that he had won the election.

Mr. Trump’s White House, at least for the bulk of his time in office, operated far differently than previous ones. Other presidents, at least according to their briefers, rarely, if ever, kept documents from their intelligence briefings.

“In my entire time of briefing President Bush, he asked to keep only one thing, which was a chart of those responsible for 9/11, which he then, when we captured or killed somebody on that list, he would cross off,” said Michael J. Morell, the former deputy director of the C.I.A., who was also an agency analyst who delivered President George W. Bush’s daily intelligence briefing.

Mr. Bush was careful about the storage of classified material, Mr. Morell said, and never took the chart out of the Oval Office.

But former intelligence officials said Mr. Trump did not have the same appreciation of the sensitivity of intelligence as Mr. Bush, whose father, George H.W. Bush, served not only as president but also, earlier in his career, as C.I.A. director.

Ms. Gordon, the former intelligence official, said when Mr. Trump’s briefers could predict his interests, they could prepare a document with sensitive sourcing information removed. That was critical, she said, because Mr. Trump never took the need to protect such material seriously.

After taking office, President Biden cut Mr. Trump off from the intelligence briefings traditionally available to former presidents. While in office, Mr. Trump needed the most sensitive intelligence, but Ms. Gordon noted that was not the case anymore.

“He is no longer the president,” Ms. Gordon said. “He no longer has a need to know. And on top of that he is not a person who is careful, nor does he understand the importance of keeping intelligence secret. That creates a very explosive cocktail.”