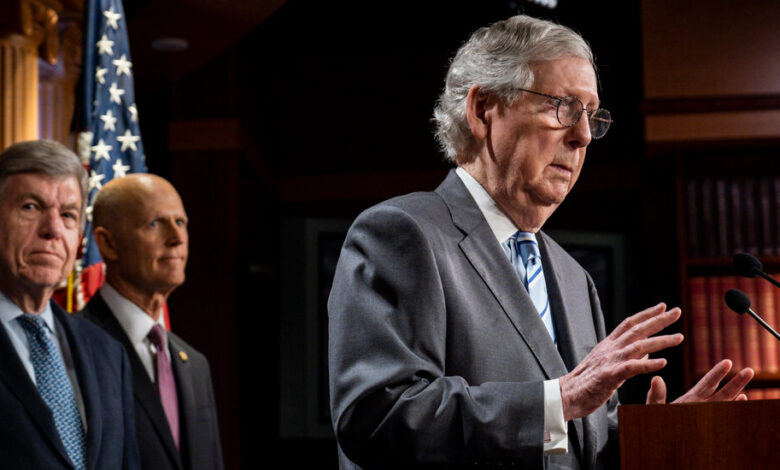

With Midterms Looming, McConnell’s Woes Pile Up

WASHINGTON — Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the minority leader, spent the summer watching Democrats score a series of legislative victories of the sort he once swore he would thwart.

His party’s crop of candidate recruits has struggled to gain traction, threatening his chances of reclaiming the Senate majority.

And this week, his dispute with the leader of the Republicans’ Senate campaign arm escalated into a public war.

As the Senate prepares to return to Washington next week for a final stint before the midterm congressional elections, Mr. McConnell is entering an autumn of discontent, a reality that looks far different from where he was expecting to be at the start of President Biden’s term.

Back then, the top Senate Republican spoke of dedicating himself full time to “stopping this new administration” and predicted that Democrats would struggle to wield their razor-thin majorities, giving Republicans an upper hand to win back both the House and the Senate.

Instead, the man known best for his ability to block and kill legislation — he once proclaimed himself the “grim reaper” — has felt the political ground shift under his feet. Democrats have, in the space of a few months, managed to pass a gun safety compromise, a major technology and manufacturing bill, a huge veterans health measure, and a climate, health and tax package — either by steering around Mr. McConnell or with his cooperation.

At the same time, the Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade appears to have handed Democrats a potent issue going into the midterm elections, brightening their hopes of keeping control of the Senate.

Mr. McConnell has acknowledged the challenges. He conceded recently that Republicans had a stronger chance of winning back the House than of taking power in the Senate in November, in part because of “candidate quality.”

The comment was widely interpreted to reflect Mr. McConnell’s growing concern about Republicans’ roster of Senate recruits, heavily influenced by former President Donald J. Trump and his hard-right supporters, who have earned Mr. Trump’s endorsement but appear to be struggling in competitive races.

It also hinted at a more basic problem that has made Mr. McConnell’s job all the more difficult: his increasingly bitter rift with Mr. Trump, which has put him at odds with the hard-right forces that hold growing sway in the Republican Party.

More Coverage of the 2022 Midterm Elections

- An Upset in Alaska: Mary Peltola, a Democrat, beat Sarah Palin in a special House election, adding to a series of recent wins for the party. Ms. Peltola will become the first Alaska Native to serve in Congress.

- Evidence Against a Red Wave: Since the fall of Roe v. Wade, it’s hard to see the once-clear signs of a Republican advantage. A strong Democratic showing in a New York special election is one of the latest examples.

- G.O.P.’s Dimming Hopes: Republicans are still favored in the fall House races, but former President Donald J. Trump and abortion are scrambling the picture in ways that distress party insiders.

- Digital Pivot: At least 10 G.O.P. candidates in competitive races have updated their websites to minimize their ties to Mr. Trump or to adjust their uncompromising stances on abortion.

“Why do Republicans Senators allow a broken down hack politician, Mitch McConnell, to openly disparage hard working Republican candidates for the United States Senate,” Mr. Trump wrote in a social media post last month that also took aim at Mr. McConnell’s wife, Elaine Chao, calling her “crazy.” Ms. Chao served as transportation secretary in the Trump administration until she abruptly resigned after the Jan. 6 attack.

Anti-Trump conservatives argue that Mr. McConnell put himself in an untenable position by failing to fully repudiate Mr. Trump after the assault on the Capitol, when the Kentucky Republican could have engineered a conviction at Mr. Trump’s impeachment trial, removing him and barring him from holding office again.

“It’s like the zombie movie where he comes back to haunt and horrify you,” said Bill Kristol, the conservative columnist. Mr. McConnell, he said, “thought he could have a good outcome legislatively and politically in 2022 without explicitly pushing back on Trump. That was the easier course. It may turn out to be a very self-defeating course for him.”

Mr. McConnell and his aides have said he is simply playing the long game, doing what he needs to to preserve the filibuster, which Democrats have repeatedly threatened to dismantle to push through their agenda. And his Senate colleagues say Mr. McConnell is not bothered by Mr. Trump’s broadsides, though he is aware that a bloc of his members is heavily influenced by the former president.

Still, the troubles come at what was supposed to be a celebratory moment for Mr. McConnell, who has been in legacy-building mode, talking about eclipsing former Senator Mike Mansfield, Democrat of Montana, as history’s longest-serving leader of either party and participating in an authorized biography for which he has opened up his archives.

“Mitch cares very deeply for the institution, and there’s probably not anything more important to him than preserving the filibuster,” said Senator Thom Tillis, Republican of North Carolina.

He said it was not Mr. McConnell who had changed, but the Senate itself, with its 50-50 partisan breakdown.

“This is the Mitch McConnell that I met in 2013 when I was considering running for the Senate,” Mr. Tillis said. “Mitch McConnell’s mentality hasn’t changed since he was playing Little League Baseball.”

That may be part of the issue. Mr. McConnell has had a nasty break with Senator Rick Scott of Florida, the chairman of the party campaign committee, who has styled himself in Mr. Trump’s image, recruited candidates loyal to the former president, visited him regularly in Florida and New Jersey, and this week attacked Mr. McConnell, without naming him, for questioning those candidates’ chances.

“Unfortunately, many of the very people responsible for losing the Senate last cycle are now trying to stop us from winning the majority this time by trash-talking our Republican candidates,” Mr. Scott wrote, calling such remarks “cowardice” and “treasonous.”

At the same time, Mr. McConnell, who has long been regarded as a master legislative tactician and relentless obstructionist, has drawn criticism from within his own ranks for striking compromises with Democrats, including on the gun safety bill and the manufacturing measure. Mr. McConnell has made plain that he views such deals as necessary to win back suburban voters in politically competitive areas.

“I’m not in favor of doing nothing at any point, no matter who gets elected,” he said at a Chamber of Commerce lunch in Kentucky earlier this week. “I’ve always felt that we could make bipartisan progress for the country within a 40-yard line.”

Senator Shelley Moore Capito, Republican of West Virginia, defended Mr. McConnell, saying he could be a “partisan warrior” when he needed to be. “He’s obviously spending a lot of time and energy to win control of the Senate,” she said.

But Mr. McConnell has also had less success of late with his attempts to block aspects of Democrats’ agenda that he opposes. He tried and failed to scuttle their sweeping climate, health and tax package by threatening to withhold Republican support for the technology and manufacturing bill if Democrats insisted on pushing it through.

The threat angered Senator Joe Manchin III, the centrist West Virginia Democrat who had been holding out on the climate package, according to a person familiar with his thinking, and stiffened Mr. Manchin’s determination to salvage it. Democrats were ultimately able to win passage of the technology measure with support from a bloc of Republicans including Mr. McConnell, and just hours later, announced a surprise deal with Mr. Manchin that would allow them to enact their legislation to cut carbon emissions, reduce the deficit and cap prescription drug costs.

Mr. McConnell’s aides have played down the significance of his comment about “candidate quality,” arguing that it was designed to spur donors to help underfunded Republicans in the homestretch of the campaign. Mr. McConnell subsequently hosted a fund-raiser in Louisville, Ky., for three Republican Senate candidates: Herschel Walker, the candidate in Georgia; Dr. Mehmet Oz, the candidate in Pennsylvania; and Representative Ted Budd of North Carolina.

“Leader McConnell’s been on airplanes and on the phone all month, and that helped make August the biggest month of the cycle so far,” said Jack Pandol, a spokesman for the Senate Leadership Fund, the political action committee Mr. McConnell controls, which has become the main vehicle for donors to support Republican candidates.

Privately, some Senate campaign operatives have sharply criticized Mr. Scott, saying they were befuddled by his decision to embark last month on an Italian yacht vacation at the same time that the committee was pulling television ad reservations in critical states, signaling it was losing hope of victories there. The trip was reported by Axios.

The bad blood has only served to underscore the party’s waning hopes of winning a Senate majority.

“I’m sitting at the leadership table with both of them every Monday night — there’s been tension,” Ms. Capito said. “Obviously there are some deep-seated bad feelings, and that’s very unfortunate.”