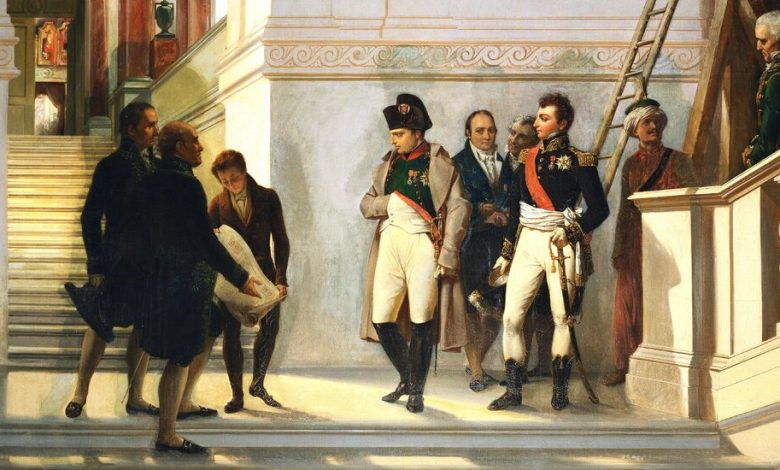

Napoleon’s Loot: When the World Decided Stolen Art Should Go Back

In September 1815, Karl von Müffling, the Prussian governor of Paris, presented himself at the doors of the Louvre and ordered its French guards to step aside.

Belgian and Dutch officials, backed by Prussian and British troops, had arrived to reclaim art treasures plundered by the French during the revolutionary and Napoleonic wars.

This moment is recognized by many scholars as a sea change in political attitudes toward the spoils of war and is seen as the birth of repatriation, the concept of returning cultural goods taken in times of conflict to the countries from which they were stolen.

“It had been universally accepted that the winners in war could take what they pleased,” said Wayne Sandholtz, who teaches international relations and law at the University of Southern California and is the author of the book “Prohibiting Plunder: How Norms Change.” “Now, for the first time, the allies demanded that the treasures be returned.”

The return of the Napoleonic loot is such a critical moment in art history that 200 years later it resurfaces again and again as debates over repatriation continue.

Three years ago, an exhibition in Paris, “Napoleon,” at the Grande Halle de la Villette focused on the French emperor’s vast spoils and efforts to reclaim them. Last year, during an exhibition on looting at the Mauritshuis in The Hague, officials there disclosed that although Napoleon returned much of the Dutch art he stole, dozens of other works were never given back.